In-depth Written Interview

Insights Beyond the Slideshows

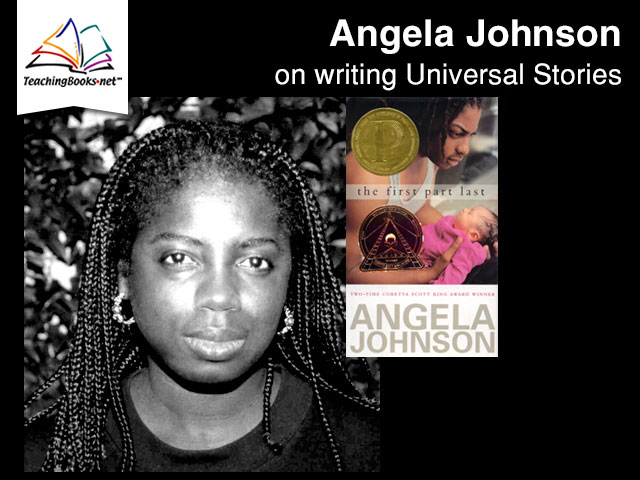

Angela Johnson interviewed while in Madison, Wisconsin on October 6, 2005.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You've won the Coretta Scott King Author Award three times — for

Toning the Sweep,

Heaven and

The First Part Last. Your book,

Heaven was written before

The First Part Last but is a sort of prequel to it. How did you come to write

The First Part Last after having already written

Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: The wonderful thing about

The First Part Last is I didn't want to write the book at all. As far as I'm concerned, I don't do prequels; I don't do sequels.

Then, I went to New York and visited some after-school programs for a

week. I was on the subway and there was this beautiful kid. He looked

about 15 or 16, and he was with a baby. It was 11:00 in the morning, and

I was thinking, "Why is this kid not in school? Is this his daughter;

is this his sister? What's the deal?"

The train stopped, and he got ready to get off the train, I actually

wanted to follow this kid down the street and question him. Something

came over me. I went back to the hotel and wrote three chapters of what

became

The First Part Last. I felt provoked, and I didn't want it to happen. Sometimes it just comes over you and there is the story or the character.

The First Part Last was the easiest book I've ever written. Bobby was just there. Everything was there.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The First Part Last, like many of your books, carries some heavy messages, though your writing never comes off as preachy.

ANGELA JOHNSON: Preaching to teens about teenage pregnancy is like preaching to a lamp. These are human beings, and they do what they want.

The First Part Last is definitely a cautionary tale, but

it's not preachy. Bobby loves his baby, but what has he lost? He's lost

the love of his life at 16. He's lost many of his freedoms. His friends

still love him, but he's lost part of that relationship. He's lost being

a child, because he is now the daddy. I always figure, show what's real

— you don't have to preach. I love Bobby's responsibility. He has

almost a romantic belief that, "I've lost Nia, so I'm going to raise

this baby." It's noble. But then reality sets in, and some of it is not

pretty.

The majority of parents have said they like

The First Part Last.

But, I have had parents say, "I'm not letting my kid read this book

because it'll give them ideas." I said, "Ideas about going into a coma?

Ideas about having this baby who's weighed you down and you've lost your

childhood?" I mean, which idea? Obviously these people haven't read the

book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Will you write about any other characters from

Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: Yes. One more book — it's called

Sweet.

It's about Shoogy. Shoogy is still unknowable to me. I'm writing about

her, and yet I still don't really know her. She is an enigma.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also write and have written many picture books. Where did your idea for

A Sweet Smell of Roses emerge from?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I based the two little girls in

A Sweet Smell of Roses on two real little girls who had marvelous spirit and participated in civil rights marches. In the documentary called

Eyes on the Prize,

two women were interviewed who were around seven and eight during the

civil rights movement. They shared their experiences about how they

would go off to marches without their parents. The wonderful thing is,

the adults around them took care of them as if they were their own

children.

Something really interesting happened in the creation of

A Sweet Smell of Roses.

In creating picture books, there's usually little or no collaboration

between author and artist. The illustrator, Eric Velasquez, was selected

by my editor; I never did share anything to him about why I wrote the

book. Would you believe, Eric included artwork from the

Eyes on the Prizedocumentary, and he wrote a foreword for the book about the documentary's filmmaker. It's just this bizarre kismet.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Several of your books don't have happy endings. How do you respond when people point this out?

ANGELA JOHNSON: At the end of some of my books,

everything is not always happiness and light. Life is not always this

big, jolly party. It is just life, and it just goes on. But I always

like to leave the end as a beginning. It's not necessarily happy, and

it's not necessarily sad. It is just life. I'm a happy person, but I'm a

realist and I write contemporary realism.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also like to include humor in your books.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe there should be more fun

books with African-American children in them. We're inundated with

family stories and folk tales and the happy family. I understand that; I

write those books, too. But there has to be a place for humor.

I love humor in any way, shape or form.

Where Have You Gone, Vivian Dartow

is going to be my funny book. Writing this book, I relived high school

all over again — I thought I had it down, and in reality, I was just the

biggest nerd.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you're stuck?

ANGELA JOHNSON: When I have trouble writing, I do

everything but write. I like to travel when I'm blocked, and I usually

come out of writing blocks after I travel.

As it turns out, my books are usually geographically motivated. I wrote

A Cool Moonlightwhen

I was in Aruba. I was on a beach with lots of sunlight writing a book

about a child who can't go out in the daylight. I had just come back

from Cape Cod when I wrote

Looking for Red.

The First Part Last came from New York, and

Toning the Sweep came from when I was in the desert with my brother. Bird is the one book that was written when I was loving being at home.

There's always going to be something in life that will ignite you. I

always believe that. It's going to be a newspaper article. It's going to

be something you heard at the supermarket. It's going to be something

you felt when you were going for a walk.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What other influences make their way into your writing?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have two nieces and a nephew. When

they were much younger, their presence in my life had an interesting

effect on my writing. I took care of them a lot, and it gave me a sense

of the world of children. It was wonderful. As they get older, I see

myself writing books for older children.

It has always been important in my books that the adults can be even a

little emotionally neglectful or just living their lives, but in the

end there is a safety net with them. In a wonderfully healthy

adolescence and teen world, your parents are there — they're supportive,

they're loving, they're not too obnoxious — and you go on about your

life. When you're home, you're secure and they're there and they leave

you alone and then you go out again. I had a huge safety net in my

parents as a teenager.

Every book has pieces from my life. For instance, all my nieces and

nephews are biracial. I have gay friends who have children. I had a

friend whose child ran away. I take looks around me. Another example is

that a female friend of mine died, and one of her children kept thinking

she saw her, as a ghost out in the garden. There are so many things

that I've incorporated in my books. Obviously, these are subjects that I

care about and are important.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to talk with students about?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I always ask if any of them journal.

I find journaling is a touchstone. When kids do that, they are secure

in their writing. There are kids who, as far as they're concerned,

writing stops when they leave the school. But, there are kids who are

putting down any feelings they have; they're raging on paper. I say not

everyone is going to be a writer, but everyone can write. No one ever

has to see what they've written.

I tell them "We're not all going to be published, but your emotions —

all of you have such strong emotions! Start journaling and become

comfortable with what you feel. Write it down and remember. If nothing

else, when you're 40 you can laugh about it like I do when I look back

at mine."

TEACHINGBOOKS: What sorts of things happen when young people write-?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I'm amazed by teen poets — the

poetry slams are just amazing. I am in love with the idea of teenagers

getting up there and just going for it. The kids who are participating

in poetry slams are the ones with something deep about them, and in

recent years, now have this incredible outlet.

When I was in school, if there were some guys who were poets, I

didn't know it. Now you're seeing these young men who are. I love that

they're being handed the power to do something positive.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Have you ever run up against censorship of your books?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have been asked not to come on author visits. I don't know that I have been banned.

One private religious school asked me not to come because in

Toning the Sweep

I talk about lynching — not graphically, of course, but I do talk about

lynching. Even though I was going to speak to their elementary-aged

children, who were too young to have read the book, they said, "We just

need to know that you will not mention that book." I said, "No, I'm

sorry, I can't do that." So they asked me not to come.

Last year in Michigan, I was speaking to a library reading club, and a

couple days before I came, the aide associated with the club decided to

call the parents and tell them that in

The First Part Last,

which was one of the books that the kids were reading, I had "language."

She made calls to the library board, she called the parents, and she

got nothing. Everyone felt the book was age-appropriate — what kids

don't speak like this?

The reasons for banning books are just ludicrous to me. It's

interesting to me that the last thing that is banned is always violence.

Sexuality, language and content are banned. Violence is not. You can

blow up a few buildings, and you can have people dragged down the

street. People will stick guns in their children's hands and send them

out in the woods to shoot animals, but they don't want to hear about

sex. It's so ridiculous.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe your writing process.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I like to write longhand on legal

pads. I just stick my legal pad in my backpack and go down to the park.

Nowadays, everybody's in the coffeehouses on their laptops. That really

freaks me out. I just started with a computer a couple years ago, but I

think I'll always have the legal pads with me as well.

I lost the first half of

Toning the Sweep on a word

processor with no hard drive in it. It was before I understood about

hard copies. I lived in a neighborhood next to an elementary school that

always used to blow the electricity. At least twice a day the

electricity on the whole street would go out. And there I was, page 47, I

remember it vividly, had not printed anything. Everything was saved on a

disk. I didn't push the little "s." The electricity went out, and it

was all gone.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to write in such a wide variety of formats (picture books, poetry, novels)?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I lucked out in the beginning of my

career with my editor, Richard Jackson. He never told me that I had to

make choices. He never said, "You write picture books." There was never a

time when he said, "You can't write poetry or short stories." I have a

collection of short stories. I wrote board books. Anything I wrote, he

said, "Okay."

Then, I started meeting other writers and saw that there are people

who just write novels. I know I sound naïve, but I was surprised that

they just write novels or they just write picture books or they just

write poetry. I thought it was a given to write whatever I felt like,

and I thought everyone did it. There are no parameters for me, which is

wonderful. The only thing I won't touch is adult literature. But as far

as kids' stuff is concerned, preschool to teen and all forms in between

are great.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you believe is the importance of writing books with African-American protagonists?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I can equate it to the first time I

was in school and I picked up a book by Ezra Jack Keats. I opened a book

and there were children who looked like me. I cannot tell you the world

that opened up. When I was a child, Ezra Jack Keats' books were the

only ones with African American children in them.

What he was doing was looking out his window and these were the

children he was seeing. It doesn't matter that he was white. There was a

little girl in a tiny library in Ohio — me — who opened up this book

and saw someone who had my skin color.

In all my books, though the stories are universal, the protagonist

will likely be an African-American child, because I remember that

feeling of being in a sea of books where no one looked like me. My

textbooks did not have any African American children. Finally in the

'70s I started to see books with African-American child protagonists,

including the book

Cornbread, Earl and Me.

Even though I want this to be a universal experience, I love the idea

that there is an African-American child saying, "This belongs to me.

Someone has recognized that kids who look like me are important and

valid."

I've gone to schools that were mostly white, and I've had children

ask me, "Why do you just write books with black children?" I say, "I'm

African American, and I'm writing through my eyes." And then I say,

"When you go into your library, how many books do you pick up that have

kids who look just like you?" And they always say, "Yeah, there are a

lot of them, aren't there?" Then I say, "Don't you think you need a few

more like these, too?" And they say, "Yeah, okay."

TEACHINGBOOKS: Despite an emphasis on African-American characters, the themes and emotional journeys in your books strike a universal chord.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe we're all connected. One

of the big problems in this country is people don't always feel that

they are connected. We're all on this road together, bumping into each

other, and we're all so connected. We have been thrown in this place.

There has to come a time where we say, "It doesn't really matter if he's

black or if he's Asian or if he's white. This is a universal story."

In the end what I want is for anyone to be able to pick up one of

these books and it doesn't matter: the color of the children, where they

live. All of these stories are everyone's story. If anyone can pick my

book up and say, "Yes, this is just a wonderful story; I've felt this; I

knew someone who felt this," then I've done what I was supposed to do.

What else is there? It's great. It's better than ice cream.