AGENDA:

EQ: How do you show how a protagonist grows and changes through the course of a story?

Today is a Writing Day. Please work on your House on Mango Street vignettes. Develop your stories to show the growth of the central character from the beginning to the end of the series of vignettes.

Remember that the 8-10 short vignettes taken together form one larger story about your protagonist.

Remember that good stories contain CONFLICT: Person vs. person, person vs. self, person vs. nature, person vs. society.

Your protagonist needs to have a goal or objective, must face an obstacle, and then may succeed or fail at achieving the goal, but learns something or changes along the way!

Go over these questions as you develop your vignettes:

1. What does the protagonist want in his or her life? What does the protagonist dream about?

2. What obstacles does the protagonist face?

3. Who are the members of the protagonist's family? Friends? Other important people (mentors) in his or her life? Who can help the protagonist achieve his or her goals?

4. What are the high points or low points in the protagonist's life?

5. Finally, for your last vignette consider how the protagonist has grown or changed from the beginning of the stories to the end. What has the protagonist learned about life?

You may also work on your House on Mango Street CHARACTER CHART and STUDY GUIDE QUESTIONS. These will be due on Monday.

HMWK: Finish reading House on Mango Street. STUDY GUIDE questions will be due on Monday. There will also be a short matching quiz on the characters in the book.

This course will serve as an introduction to the basic grammatical rules of standard written English through the use of writing exercises and creative activities. Students will review basic grammar and move on to more advanced stylistic concerns essential to creative writers in all genres. 2nd semester--writing for self-discovery

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

House on Mango Street/Vignettes

AGENDA:

BELL WORK: Work on Character List for the stories up to pg. 48 in House on Mango Street. You may work with a partner, but keep a list for yourself. There will be a quiz on the characters and their relationship to Esperanza.

In your reading groups, read aloud pg. 49-61 (4 stories) in House on Mango Street.

Add these characters to your list.

Discuss these questions after you read each story and post a comment for your reading group.

"Hips"

1. What are the girls doing as they talk about hips? What are hips good for? What does their conversation tell you about their ages?

"The First Job"

Why does this story have a misleading title? What happens to Esperanza on her first day at work? What does this episode tell you about her family and their expectations?

"Papa Who Wakes Up Tired in the Dark"

Why does Esperanza's father cry? How does his crying make her feel?

"Born Bad"

What happens to Aunt Lupe? Why does Esperanza believe she deserves to go to hell? What special relationship did Esperanza have with her aunt?

Major Themes

Minor Theme Love

MOOD

SETTING

The setting of the story is a poor Hispanic neighborhood in Chicago.

Judging from the cars people drive, it is probably the 1960’s. The neighborhood

is very close-knit, full of immigrants who do not speak English well and

rarely leave the neighborhood.

Conflict

Protagonist / Antagonist

Esperanza, the protagonist, has no real antagonist except, perhaps,

herself. The story concerns her journey to maturity (bildungsroman, "coming of age"). Conflicts in the

story often arise because of Esperanza’s misunderstanding of herself.

For example, she makes fun of her sick aunt, then realizes how much she

values her aunt’s friendship, and feels terrible about what she has done.

Her shyness is another aspect of her immaturity that forces conflict upon

her: she wants to be like bolder girls she knows, who have secret meetings

with boys, but does not have the courage. Additionally, Esperanza must

mature enough to discover her own identity, and understand how the Mango

Street she hates so much fits into her life.

WRITING: Period 4

Continue working on your own stories.

BELL WORK: Work on Character List for the stories up to pg. 48 in House on Mango Street. You may work with a partner, but keep a list for yourself. There will be a quiz on the characters and their relationship to Esperanza.

In your reading groups, read aloud pg. 49-61 (4 stories) in House on Mango Street.

Add these characters to your list.

Discuss these questions after you read each story and post a comment for your reading group.

"Hips"

1. What are the girls doing as they talk about hips? What are hips good for? What does their conversation tell you about their ages?

"The First Job"

Why does this story have a misleading title? What happens to Esperanza on her first day at work? What does this episode tell you about her family and their expectations?

"Papa Who Wakes Up Tired in the Dark"

Why does Esperanza's father cry? How does his crying make her feel?

"Born Bad"

What happens to Aunt Lupe? Why does Esperanza believe she deserves to go to hell? What special relationship did Esperanza have with her aunt?

Focus on Themes, Mood, Setting, and Conflict. How will your stories connect and convey theme, mood, setting and conflict?

Major Themes

Maturity

The main theme of the book is Esperanza’s increasing maturity. It is in evidence throughout the book, as Esperanza talks to older female characters, trying to determine who her role models will be, or as she overcomes her insecurities and learns about her own strengths and weaknesses.

Home and IdentityThroughout the book, Esperanza attaches meaning to where she lives: she takes it personally as an extension of herself. Thus, the fact that she is unhappy and ashamed at her Mango Street house is a major point of contention in the book, and her dreams of another home parallel her dreams of becoming who she wants to be.

Minor Theme Love

Though it is not discussed directly in the book, love of different kinds, between different characters, holds many relationships together. Family love is contrasted with romantic love, and mistaken ideas about what love is (particularly as concern Marin and Sally) are prominent in the book.

MOOD

The mood of the story is highly influenced by Esperanza’s own mood, and the mood of the story is uneven to reflect Esperanza’s uneven moods. When she is happy, as in "Our Good Day," the mood is joyous, relaxed, and untroubled. When she is frightened or hurt, as in "Red Clowns," the mood reflects that. Esperanza has a complex personality, so the mood ranges from childish temper tantrums to solemn thoughtfulness. In general, this indicates Esperanza’s place in the world: intelligent, but not yet fully grown up. The mood is childish and adult by turns.

SETTING

The setting of the story is a poor Hispanic neighborhood in Chicago.

Judging from the cars people drive, it is probably the 1960’s. The neighborhood

is very close-knit, full of immigrants who do not speak English well and

rarely leave the neighborhood.Conflict

Protagonist / Antagonist

Esperanza, the protagonist, has no real antagonist except, perhaps,

herself. The story concerns her journey to maturity (bildungsroman, "coming of age"). Conflicts in the

story often arise because of Esperanza’s misunderstanding of herself.

For example, she makes fun of her sick aunt, then realizes how much she

values her aunt’s friendship, and feels terrible about what she has done.

Her shyness is another aspect of her immaturity that forces conflict upon

her: she wants to be like bolder girls she knows, who have secret meetings

with boys, but does not have the courage. Additionally, Esperanza must

mature enough to discover her own identity, and understand how the Mango

Street she hates so much fits into her life. WRITING: Period 4

Continue working on your own stories.

Friday, October 24, 2014

Brainstorming for "House on (your title) Street" Vignettes

AGENDA:

EQ: What key moments in my life will be interesting to write about in vignette form?

ACTIVITIES: Brainstorming.

Using the high/low handout and/or timeline handout, plot out key moments in your life.

What are your dreams (clouds)?

What are your high points (Mountains)?

What are your low points (valleys)?

What are your every day activities (River of life)?

Also, you can go online and look at "have you ever" questions. These are good starters, as well as the following questions.

Don't forget about characterizations. WHO are the best/worst/craziest/smartest/most interesting/silliest/ weirdest people in your life--family, friends, neighbors, etc?

Where in the world have you been that you thought was paradise?

What is your favorite bumper sticker?

Weirdest thing you have ever eaten?

What is your pet peeve?

What makes a good friend? Who is your best friend?

What part of society needs to be cleaned up?

Who is the worst actor in Hollywood?

Name a time when you got into big trouble with your parents.

When you were small – which superhero did you like?

Can you fake any accents?

I am not trying to embarrass you, but, do you have an embarrassing guilty pleasure?

You wouldn’t be caught dead, where?

What is the kindest thing that someone has ever done for you?

If you had a time machine that could take you back in time – what year would you go to and why?

Do you have any hidden talents?

How far east can you go before you're heading west?

Most hated chore on the household chore list?

Which bad habits of other people drive you crazy?

Name two things you consider yourself to be very good at.

Name two things you consider yourself to be very bad at.

Which kind of puppies do you hate the most?

What is the stupidest habit that mankind participates in regards to the environment?

Is there anything you absolutely refuse to do under any circumstances?

Where is your bloodline originally from?

If you had to, what family member would you kill off and why?

BEGIN WRITING YOUR VIGNETTES. TRY TO IMITATE CISNEROS' STYLE BY USING METAPHORS, SIMILES,

REPETITION, AND THE ELEMENTS OF PROSE POETRY.

EQ: What key moments in my life will be interesting to write about in vignette form?

ACTIVITIES: Brainstorming.

Using the high/low handout and/or timeline handout, plot out key moments in your life.

What are your dreams (clouds)?

What are your high points (Mountains)?

What are your low points (valleys)?

What are your every day activities (River of life)?

Also, you can go online and look at "have you ever" questions. These are good starters, as well as the following questions.

Don't forget about characterizations. WHO are the best/worst/craziest/smartest/most interesting/silliest/ weirdest people in your life--family, friends, neighbors, etc?

Where in the world have you been that you thought was paradise?

What is your favorite bumper sticker?

Weirdest thing you have ever eaten?

What is your pet peeve?

What makes a good friend? Who is your best friend?

What part of society needs to be cleaned up?

Who is the worst actor in Hollywood?

Name a time when you got into big trouble with your parents.

When you were small – which superhero did you like?

Can you fake any accents?

I am not trying to embarrass you, but, do you have an embarrassing guilty pleasure?

You wouldn’t be caught dead, where?

What is the kindest thing that someone has ever done for you?

If you had a time machine that could take you back in time – what year would you go to and why?

Do you have any hidden talents?

How far east can you go before you're heading west?

Most hated chore on the household chore list?

Which bad habits of other people drive you crazy?

Name two things you consider yourself to be very good at.

Name two things you consider yourself to be very bad at.

Which kind of puppies do you hate the most?

What is the stupidest habit that mankind participates in regards to the environment?

Is there anything you absolutely refuse to do under any circumstances?

Where is your bloodline originally from?

If you had to, what family member would you kill off and why?

BEGIN WRITING YOUR VIGNETTES. TRY TO IMITATE CISNEROS' STYLE BY USING METAPHORS, SIMILES,

REPETITION, AND THE ELEMENTS OF PROSE POETRY.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Poetic Prose Vignettes/Sandra Cisneros

AGENDA:

EQ: What are the qualities of a poetic vignette?

BELLWORK: Parts of Speech Review

1. Presentations for The FIRST PART LAST continued

2. DISCUSSION: Review Cisneros vignettes from last class

http://www.enotes.com/topics/house-on-mango-street

3. WRITING: Begin your House on My Street vignette book

The House on Mango Street is a deceptive work. It is a book of short stories—and sometimes not even full stories, but character sketches and vignettes—that add up, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "to tell one big story, each story contributing to the whole—like beads in a necklace." That story is told in language that seems simple but that possesses the associative richness of poetry, and whose slang and breaks from grammatical correctness contribute to its immediacy. It is narrated in the voice of a young girl—a girl too young to know that no one may ever hear her—but whose voice is completely convincing, because it is the creation of a mature and sophisticated writer. For example, The House on Mango Street appears to wander casually from subject to subject—from hair to hips, from clouds to feet, from an invalid aunt to a girl named Sally, who has "eyes like Egypt" and whose father sometimes beats her. But this apparent randomness disguises an artful exploration of themes of individual identity and communal loyalty, estrangement and loss, escape and return, the lure of romance and the dead end of sexual inequality and oppression.

The House on Mango Street is also a book about a culture—that of Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans—that has long been veiled by demeaning stereotypes and afflicted by internal ambivalence. In some ways it resembles the immigrant cultures that your students may have encountered in books like My Ántonia, The Jungle, and Call It Sleep. But unlike Americans of Slavic or Jewish ancestry, Chicanos have been systematically excluded from the American mainstream in ways that suggest the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Although Cisneros uses language as a recurring metaphor for the gulf between Mexican-Americans and the majority culture, what keeps Esperanza Cordero and her family and friends locked in their barrio is something more obdurate than language: a confluence of racism, poverty, and shame. It may help your discussion to remind students that the ancestors of many Chicanos did not come to the United States by choice, but simply found themselves in alien territory as a result of the U.S.'s expansionist policy into country that had once been Mexican.

But although The House on Mango Street will have a particularly strong appeal to Latino students, who may never have encountered a book that speaks so pointedly to their own experience, it is a work that captures the universal pangs of otherness—what Cisneros, in her introduction to the tenth anniversary edition (published by Knopf, $18.00), has called "the shame of being poor, of being female, of being not-quite-good-enough." It suggests from where that otherness comes and shows how it can become a cause for celebration rather than shame. Few students, regardless of their ancestry or gender, will come away from this book without a strong sensation of having glimpsed a secret part of themselves. For, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "You, the reader, are Esperanza.... You cannot forget who you are."

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. She has worked as a teacher to high school dropouts, a poet-in-the-schools, a college recruiter, and an arts administrator. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, and the recipient of numerous awards, Cisneros is also the author of Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories, My Wicked Wicked Ways, and Loose Woman. The daughter of a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother, and sister to six brothers, she is nobody's mother and nobody's wife. She lives in San Antonio, Texas, and is currently at work on a novel.

HMWK: Read to pg. in House on Mango Street

EQ: What are the qualities of a poetic vignette?

BELLWORK: Parts of Speech Review

1. Presentations for The FIRST PART LAST continued

2. DISCUSSION: Review Cisneros vignettes from last class

http://www.enotes.com/topics/house-on-mango-street

3. WRITING: Begin your House on My Street vignette book

The House on Mango Street is a deceptive work. It is a book of short stories—and sometimes not even full stories, but character sketches and vignettes—that add up, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "to tell one big story, each story contributing to the whole—like beads in a necklace." That story is told in language that seems simple but that possesses the associative richness of poetry, and whose slang and breaks from grammatical correctness contribute to its immediacy. It is narrated in the voice of a young girl—a girl too young to know that no one may ever hear her—but whose voice is completely convincing, because it is the creation of a mature and sophisticated writer. For example, The House on Mango Street appears to wander casually from subject to subject—from hair to hips, from clouds to feet, from an invalid aunt to a girl named Sally, who has "eyes like Egypt" and whose father sometimes beats her. But this apparent randomness disguises an artful exploration of themes of individual identity and communal loyalty, estrangement and loss, escape and return, the lure of romance and the dead end of sexual inequality and oppression.

The House on Mango Street is also a book about a culture—that of Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans—that has long been veiled by demeaning stereotypes and afflicted by internal ambivalence. In some ways it resembles the immigrant cultures that your students may have encountered in books like My Ántonia, The Jungle, and Call It Sleep. But unlike Americans of Slavic or Jewish ancestry, Chicanos have been systematically excluded from the American mainstream in ways that suggest the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Although Cisneros uses language as a recurring metaphor for the gulf between Mexican-Americans and the majority culture, what keeps Esperanza Cordero and her family and friends locked in their barrio is something more obdurate than language: a confluence of racism, poverty, and shame. It may help your discussion to remind students that the ancestors of many Chicanos did not come to the United States by choice, but simply found themselves in alien territory as a result of the U.S.'s expansionist policy into country that had once been Mexican.

But although The House on Mango Street will have a particularly strong appeal to Latino students, who may never have encountered a book that speaks so pointedly to their own experience, it is a work that captures the universal pangs of otherness—what Cisneros, in her introduction to the tenth anniversary edition (published by Knopf, $18.00), has called "the shame of being poor, of being female, of being not-quite-good-enough." It suggests from where that otherness comes and shows how it can become a cause for celebration rather than shame. Few students, regardless of their ancestry or gender, will come away from this book without a strong sensation of having glimpsed a secret part of themselves. For, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "You, the reader, are Esperanza.... You cannot forget who you are."

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. She has worked as a teacher to high school dropouts, a poet-in-the-schools, a college recruiter, and an arts administrator. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, and the recipient of numerous awards, Cisneros is also the author of Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories, My Wicked Wicked Ways, and Loose Woman. The daughter of a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother, and sister to six brothers, she is nobody's mother and nobody's wife. She lives in San Antonio, Texas, and is currently at work on a novel.

HMWK: Read to pg. in House on Mango Street

Monday, October 20, 2014

PRESENTATIONS FIRST PART LAST

AGENDA:

Period 3 Turn in Verbs Handout

Presentations in A238

Period 4

EQ: How does Cisneros

READ and Discuss:

Eleven

From Woman Hollering Creek Copyright © 1991 by Sandra Cisneros. Reprinted by permission of Susan Bergholtz Literary Services, New York. All rights reserved.

Discussion questions for Sandra Cisneros‘s “Barbie-Q”

HMWK: Read to pg. 43 for Wednesday House on Mango Street

TURN IN MONTANA 1948! Turn in The First Part Last!

Period 3 Turn in Verbs Handout

Presentations in A238

Period 4

EQ: How does Cisneros

READ and Discuss:

Eleven

By Sandra Cisneros

What they don’t understand about birthdays and what they never tell you is that when you’re eleven, you’re also ten, and nine, and eight, and seven, and six, and five, and four, and three, and two, and one. And when you wake up on your eleventh birthday you expect to feel eleven, but you don’t. You open your eyes and everything’s just like yesterday, only it’s today. And you don’t feel eleven at all. You feel like you’re still ten. And you are—underneath the year that makes you eleven.

Like some days you might say something stupid, and that’s the part of you that’s still ten. Or maybe some days you might need to sit on your mama’s lap because you’re scared, and that’s the part of you that’s five. And maybe one day when you’re all grown up maybe you will need to cry like if you’re three, and that’s okay. That’s what I tell Mama when she’s sad and needs to cry. Maybe she’s feeling three.

Because the way you grow old is kind of like an onion or like the rings inside a tree trunk or like my little wooden dolls that fit one inside the other, each year inside the next one. That’s how being eleven years old is.

You don’t feel eleven. Not right away. It takes a few days, weeks even, sometimes even months before you say Eleven when they ask you. And you don’t feel smart eleven, not until you’re almost twelve. That’s the way it is.

Only today I wish I didn’t have only eleven years rattling inside me like pennies in a tin Band-Aid box. Today I wish I was one hundred and two instead of eleven because if I was one hundred and two I’d have known what to say when Mrs. Price put the red sweater on my desk. I would’ve known how to tell her it wasn’t mine instead of just sitting there with that look on my face and nothing coming out of my mouth.

“Whose is this?” Mrs. Price says, and she holds the red sweater up in the air for all the class to see. “Whose? It’s been sitting in the coatroom for a month.”

“Not mine,” says everybody. “Not me.”

“It has to belong to somebody,” Mrs. Price keeps saying, but nobody can remember. It’s an ugly sweater with red plastic buttons and a collar and sleeves all stretched out like you could use it for a jump rope. It’s maybe a thousand years old and even if it belonged to me I wouldn’t say so.

Maybe because I’m skinny, maybe because she doesn’t like me, that stupid Sylvia Saldivar says, “I think it belongs to Rachel.” An ugly sweater like that, all raggedy and old, but Mrs. Price believes her. Mrs. Price takes the sweater and puts it right on my desk, but when I open my mouth nothing comes out.

“That’s not, I don’t, you’re not . . . Not mine,” I finally say in a little voice that was maybe me when I was four.

“Of course it’s yours,” Mrs. Price says, “I remember you wearing it once.” Because she’s older and the teacher, she’s right and I’m not.

Not mine, not mine, not mine, but Mrs. Price is already turning to page thirty-two, and math problem number four. I don’t know why but all of a sudden I’m feeling sick inside, like the part of me that’s three wants to come out of my eyes, only I squeeze them shut tight and bite down on my teeth real hard and try to remember today I am eleven, eleven. Mama is making a cake for me for tonight, and when Papa comes home everybody will sing Happy birthday, happy birthday to you.

But when the sick feeling goes away and I open my eyes, the red sweater’s still sitting there like a big red mountain. I move the red sweater to the corner of my desk with my ruler. I move my pencil and books and eraser as far from it as possible. I even move my chair a little to the right. Not mine, not mine, not mine.

In my head I’m thinking how long till lunchtime, how long till I can take the red sweater and throw it over the schoolyard fence, or leave it hanging on a parking meter, or bunch it up into a little ball and toss it in the alley. Except when math period ends Mrs. Price says loud and in front of everybody, “Now, Rachel, that’s enough,” because she sees I’ve shoved the red sweater to the tippy-tip corner of my desk and it’s hanging all over the edge like a waterfall, but I don’t care.

“Rachel,” Mrs. Price says. She says it like she’s getting mad. “You put that sweater on right now and no more nonsense.”

“But it’s not—“

“Now!” Mrs. Price says.

This is when I wish I wasn’t eleven, because all the years inside of me—ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one—are pushing at the back of my eyes when I put one arm through one sleeve of the sweater that smells like cottage cheese, and then the other arm through the other and stand there with my arms apart like if the sweater hurts me and it does, all itchy and full of germs that aren’t mine.

That’s when everything I’ve been holding in since this morning, since when Mrs. Price put the sweater on my desk, finally lets go, and all of a sudden I’m crying in front of everybody. I wish I was invisible but I’m not. I’m eleven and it’s my birthday today and I’m crying like I’m three in front of everybody. I put my head down on the desk and bury my face in my stupid clown-sweater arms. My face all hot and spit coming out of my mouth because I can’t stop the little animal noises from coming out of me, until there aren’t any more tears left in my eyes, and it’s just my body shaking like when you have the hiccups, and my whole head hurts like when you drink milk too fast.

But the worst part is right before the bell rings for lunch. That stupid Phyllis Lopez, who is even dumber than Sylvia Saldivar, says she remembers the red sweater is hers! I take it off right away and give it to her, only Mrs. Price pretends like everything’s okay.

Today I’m eleven. There’s a cake Mama’s making for tonight, and when Papa comes home from work we’ll eat it. There’ll be candles and presents and everybody will sing Happy birthday, happy birthday to you, Rachel, only it’s too late.

I’m eleven today. I’m eleven, ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one, but I wish I was one hundred and two. I wish I was anything but eleven, because I want today to be far away already, far away like a runaway balloon, like a tiny o in the sky, so tiny-tiny you have to close your eyes to see it.

From Woman Hollering Creek Copyright © 1991 by Sandra Cisneros. Reprinted by permission of Susan Bergholtz Literary Services, New York. All rights reserved.

Barbie-Q

By Sandra Cisneros

Yours is the one with mean eyes and a ponytail. Striped swimsuit, stilettos, sunglasses, and gold hoop earrings. Mine is the one with bubble hair. Red swimsuit, stilettos, pearl earrings, and a wire stand. But that’s all we can afford, besides one extra outfit apiece. Yours, “Red Flair,” sophisticated A-line coatdress with a Jackie Kennedy pillbox hat, white gloves, handbag, and heels included. Mine, “solo in the Spotlight,” evening elegance in black glitter strapless gown with a puffy skirt at the bottom like a mermaid tail, formal-length gloves, pink chiffon scarf, and mike included. From so much dressing and undressing, the black glitter wears off where her titties stick out. This and a dress invented from an old sock when we cut holes here and here and here, the cuff rolled over for the glamorous, fancy-free, off-the-shoulder look.

Every time the same story. Your Barbie is roommates with my Barbie, and my Barbie’s boyfriend comes over and your Barbie steals him, okay? Kiss kiss kiss. Then the two Barbies fight. You dumbbell! He’s mine. Oh no he’s not, you stinky! Only Ken’s invisible, right? Because we don’t have money for a stupid-looking boy doll when we’d both rather ask for a new Barbie outfit next Christmas. We have to make do with your mean-eyed Barbie and my bubblehead Barbie and our one outfit apiece not including the sock dress.

Until next Sunday when we are walking through the flea market on Maxwell Street and there! Lying on the street next to some tool bits, and platform shoes with the heels all squashed, and a fluorescent green wicker wastebasket, and aluminum foil, and hubcaps, and a pink shag rug, and windshield wiper blades, and dusty mason jars, and a coffee can full of rusty nails. There! Where? Two Mattel boxes. One with the “Career Gal” ensemble, snappy black-and-white business suit, three-quarter-length sleeve jacket with kick-pleated skirt, red sleeveless shell, gloves, pumps, and matching hat included. The other, “Sweet Dreams,” dreamy pink-and-white plaid nightgown and matching robe, lace-trimmed slippers, hair-brush and hand mirror included. How much? Please, please, please, please, please, please, please, until they say okay.

On the outside you and me skipping and humming but inside we are doing loopity-loops and pirouetting. Until at the next vendor’s stand, next to boxed pies, and bright orange toilet brushes, and rubber gloves, and wrench sets, and bouquests of feather flowers, and glass towel racks, and steel wool, and Alvin and the Chipmunks records, there! And there! And there! And there! and there! and there! and there! Bendable Legs Barbie with her new page-boy hairdo, Midge, Barbie’s best friend. Ken, Barbie’s boyfriend. Skipper, Barbie’s little sister. Tutti and Todd, Barbie and Skipper’s tiny twin sister and brother. Skipper’s friends, Scooter and Ricky. Alan, Ken’s buddy. And Francie, Barbie’ MOD’ern cousin.

Everybody today selling toys, all of them damaged with water and smelling of smoke. Because a big toy warehouse on Halsted Street burned down yesterday—see there?—the smoke still rising and drifting across the Dan Ryan expressway. And now there is a big fire sale at Maxwell Street, today only.

So what if we didn’t get our new Bendable Legs Barbie and Midge and Ken and Skipper and Tutti and Todd and Scooter and Ricky and Alan and Francie in nice clean boxes and had to buy them on Maxwell Street, all water-soaked and sooty. So what if our Barbies smell like smoke when you hold them up to your nose even after you wash and wash and wash them. And if the prettiest doll, Barbie’s MOD’ern cousin Francie with real eyelashes, eyelash brush included, has a left foot that’s melted a little—so? If you dress her in her new “Prom Pinks” outfit, satin splendor with matching coat, gold belt, clutch, and hair bow included, so long as you don’t lift her dress, right?—who’s to know.

Discussion questions for Sandra Cisneros‘s “Barbie-Q”

- What could Barbie’s wardrobe, e.g. Red Flair, Career Gal, Jackie Kennedy pillbox hat, Prom Pinks, suggest about a woman’s status in society?

- What values and ideals does Barbie represent/symbolize in the story? What does she offer the two girls in the story?

- Do you believe that Cisneros has some feminist concerns in Barbie-Q? If yes, explain what these concerns could be.

- What could the image of flawed/damaged dolls signify?

- Do you believe that Cisneros voices some racial concerns in Barbie-Q? If yes, explain what these concerns could be. Comment on the origin of the protagonists.

- What could the story tell us about the influence of hegemonic culture over the dominated?

- Discuss whether Barbie is the embodiment of women’s oppression or liberation.

- Why does Cisneros associate the title of the story with a cooking technique?

Continue to work on writing your own "House on Mango Street"

8-10 Vignettes modeled on the book but based on your own life, family, friends, neighborhood

Title your vignettes

8-10 Vignettes modeled on the book but based on your own life, family, friends, neighborhood

Title your vignettes

HMWK: Read to pg. 43 for Wednesday House on Mango Street

TURN IN MONTANA 1948! Turn in The First Part Last!

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Finish First Part Last PROJECTS for presentation!

House on Mango Street--Vignettes

2. Introduction to The House on Mango Street

Go to library and pick up book

EQ: What is a vignette?

AGENDA: Finish up First Part Last projects for presentation Monday

1. GRAMMAR: Work on VERBS handout to hand in Monday (if you are finished with other work)

1. GRAMMAR: Work on VERBS handout to hand in Monday (if you are finished with other work)

2. Introduction to The House on Mango Street

Go to library and pick up book

EQ: What is a vignette?

vi·gnette

vinˈyet/

noun

noun: vignette; plural noun: vignettes

- 1.a brief evocative description, account, or episode.

- 2.a small illustration or portrait photograph that fades into its background without a definite border.

- a small ornamental design filling a space in a book or carving, typically based on foliage.

verb

verb: vignette; 3rd person present: vignettes; past tense: vignetted; past participle: vignetted; gerund or present participle: vignetting

1.

Four Skinny Trees

"Four Skinny Trees" is an excerpt from the book by Sandra Cisneros entitled The House on Mango Street. "Four Skinny Trees" is found on pages 74 and 75. Copyright Sandra Cisneros, 1984 and published by Vintage Contemporaries, 1991.

"They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn't appreciate these things.

"Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

"Let one forget his reason for being, they'd all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

"When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete. Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be."

"They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn't appreciate these things.

"Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

"Let one forget his reason for being, they'd all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

"When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete. Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be."

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

The First Part Last Closure

AGENDA:

Quiz on The First Part Last

WRITING: Work on the First Part Last Project

Finish Partner Story

Quiz on The First Part Last

WRITING: Work on the First Part Last Project

Finish Partner Story

Thursday, October 9, 2014

The First Part Last

AGENDA:

WRITING ACTIVITY: Working with your partner, combine your BEGINNING and ENDING stories with a MIDDLE..

PERIOD 4: continue working on your FIRST PART LAST PROJECT

HMWK: Be sure you have finished the book for a quiz on TUESDAY!

Have a great weekend!

WRITING ACTIVITY: Working with your partner, combine your BEGINNING and ENDING stories with a MIDDLE..

PERIOD 4: continue working on your FIRST PART LAST PROJECT

HMWK: Be sure you have finished the book for a quiz on TUESDAY!

Have a great weekend!

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

First Part Last Projects

AGENDA:

BELL WORK:

Conjunctions and Interjections

We're almost there! Eight parts of speech. 7 down. 1 to go!

ACTIVITIES:

Begin work on First Part Last projects.

BELL WORK:

Conjunctions and Interjections

We're almost there! Eight parts of speech. 7 down. 1 to go!

ACTIVITIES:

Begin work on First Part Last projects.

Friday, October 3, 2014

Angela Johnson Links

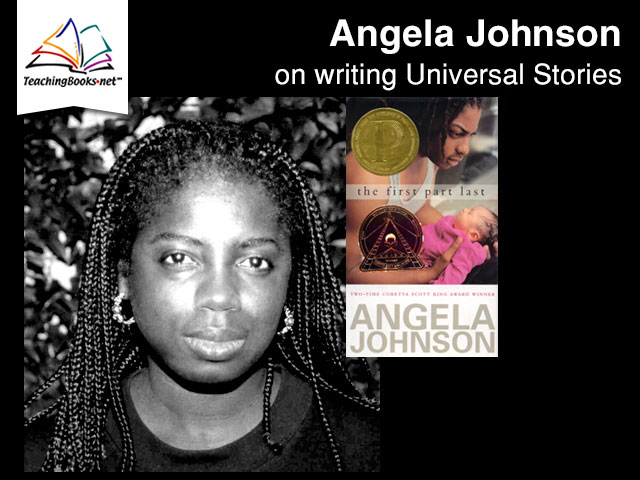

![[angela_johnson.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi-WgdizGD1mnxLz-IvmzWz_0QPpe7pJcV4HqXcTHqCAK9l8uLV7wcvEeywDNq-w8w5f4l_LYOss3VtXgx6xNC5dtk2dN9yd2Vatynml_ghJj3zZWnVoJYVR51va5y36-2rXqwJjOa-wzyd/s1600/angela_johnson.jpg)

Link to Angela Johnson:

http://authors.simonandschuster.com/Angela-Johnson/1263944

http://www.ohiochannel.org/MediaLibrary/Media.aspx?fileId=126267

http://www.ajohnsonauthor.com/

http://www.teachingbooks.net/slideshows/johnson/Reads_FirstPartLast.html

http://thebrownbookshelf.com/2009/02/08/angela-johnson/

FIRST PART LAST PROJECTS

AGENDA:

BELL WORK: PREPOSITIONS

DISCUSSION: FIRST PART LAST

Work with Think, Pair, Share partners to answer Questions for Part 3 & 4 from previous posts.

WRITING PROJECTS:

Verbal/ Linguistic

Write at least five letters to Nia explaining what is happening with both Bobby and Feather in Bobby's voice. Be specific!

or

Study the spare, lyrical writing of Angela Johnson and try to write a story with a similar quality and the same economy of words or a sense of NOW/THEN.

Creative Project:

Create a movie trailer for the book using Moviemaker or Adobe Premiere.

BELL WORK: PREPOSITIONS

DISCUSSION: FIRST PART LAST

Work with Think, Pair, Share partners to answer Questions for Part 3 & 4 from previous posts.

WRITING PROJECTS:

Verbal/ Linguistic

Write at least five letters to Nia explaining what is happening with both Bobby and Feather in Bobby's voice. Be specific!

or

Study the spare, lyrical writing of Angela Johnson and try to write a story with a similar quality and the same economy of words or a sense of NOW/THEN.

Creative Project:

Create a movie trailer for the book using Moviemaker or Adobe Premiere.

Wednesday, October 1, 2014

I Used to Be Poem

Write an Instant "I Used To..." Poem | |

Method: | |

Sample: | I used to think that summers stretched slow and lazy for a year But now I know better I always thought "school one year, summer one year" But I never counted off the days on my fingers I once felt hours stretch long and easy But now I hear a panicky tick-tock If I could step into a time machine I would go back and reset the clock I never gave it a thought before But I might seriously consider it now I can't turn life into a sci-fi movie But I can gobble up every day 'til I'm filled up happy I won't ever be 16 again But I might be a teenager at heart I used to think that summers stretched slow and lazy for a year But now I know better |

Interview with Angela Johnson

Interview w/ Angela Johnson

http://www.teachingbooks.net/author_collection.cgi?id=28&a=1

TEACHINGBOOKS: You've won the Coretta Scott King Author Award three times — for Toning the Sweep, Heaven and The First Part Last. Your book, Heaven was written before The First Part Last but is a sort of prequel to it. How did you come to write The First Part Last after having already written Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: The wonderful thing about The First Part Last is I didn't want to write the book at all. As far as I'm concerned, I don't do prequels; I don't do sequels.

Then, I went to New York and visited some after-school programs for a week. I was on the subway and there was this beautiful kid. He looked about 15 or 16, and he was with a baby. It was 11:00 in the morning, and I was thinking, "Why is this kid not in school? Is this his daughter; is this his sister? What's the deal?"

The train stopped, and he got ready to get off the train, I actually wanted to follow this kid down the street and question him. Something came over me. I went back to the hotel and wrote three chapters of what became The First Part Last. I felt provoked, and I didn't want it to happen. Sometimes it just comes over you and there is the story or the character. The First Part Last was the easiest book I've ever written. Bobby was just there. Everything was there.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The First Part Last, like many of your books, carries some heavy messages, though your writing never comes off as preachy.

ANGELA JOHNSON: Preaching to teens about teenage pregnancy is like preaching to a lamp. These are human beings, and they do what they want.

The First Part Last is definitely a cautionary tale, but it's not preachy. Bobby loves his baby, but what has he lost? He's lost the love of his life at 16. He's lost many of his freedoms. His friends still love him, but he's lost part of that relationship. He's lost being a child, because he is now the daddy. I always figure, show what's real — you don't have to preach. I love Bobby's responsibility. He has almost a romantic belief that, "I've lost Nia, so I'm going to raise this baby." It's noble. But then reality sets in, and some of it is not pretty.

The majority of parents have said they like The First Part Last. But, I have had parents say, "I'm not letting my kid read this book because it'll give them ideas." I said, "Ideas about going into a coma? Ideas about having this baby who's weighed you down and you've lost your childhood?" I mean, which idea? Obviously these people haven't read the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Will you write about any other characters from Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: Yes. One more book — it's called Sweet. It's about Shoogy. Shoogy is still unknowable to me. I'm writing about her, and yet I still don't really know her. She is an enigma.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also write and have written many picture books. Where did your idea for A Sweet Smell of Roses emerge from?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I based the two little girls in A Sweet Smell of Roses on two real little girls who had marvelous spirit and participated in civil rights marches. In the documentary called Eyes on the Prize, two women were interviewed who were around seven and eight during the civil rights movement. They shared their experiences about how they would go off to marches without their parents. The wonderful thing is, the adults around them took care of them as if they were their own children.

Something really interesting happened in the creation of A Sweet Smell of Roses. In creating picture books, there's usually little or no collaboration between author and artist. The illustrator, Eric Velasquez, was selected by my editor; I never did share anything to him about why I wrote the book. Would you believe, Eric included artwork from the Eyes on the Prizedocumentary, and he wrote a foreword for the book about the documentary's filmmaker. It's just this bizarre kismet.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Several of your books don't have happy endings. How do you respond when people point this out?

ANGELA JOHNSON: At the end of some of my books, everything is not always happiness and light. Life is not always this big, jolly party. It is just life, and it just goes on. But I always like to leave the end as a beginning. It's not necessarily happy, and it's not necessarily sad. It is just life. I'm a happy person, but I'm a realist and I write contemporary realism.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also like to include humor in your books.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe there should be more fun books with African-American children in them. We're inundated with family stories and folk tales and the happy family. I understand that; I write those books, too. But there has to be a place for humor.

I love humor in any way, shape or form. Where Have You Gone, Vivian Dartow is going to be my funny book. Writing this book, I relived high school all over again — I thought I had it down, and in reality, I was just the biggest nerd.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you're stuck?

ANGELA JOHNSON: When I have trouble writing, I do everything but write. I like to travel when I'm blocked, and I usually come out of writing blocks after I travel.

As it turns out, my books are usually geographically motivated. I wrote A Cool Moonlightwhen I was in Aruba. I was on a beach with lots of sunlight writing a book about a child who can't go out in the daylight. I had just come back from Cape Cod when I wrote Looking for Red. The First Part Last came from New York, and Toning the Sweep came from when I was in the desert with my brother. Bird is the one book that was written when I was loving being at home.

There's always going to be something in life that will ignite you. I always believe that. It's going to be a newspaper article. It's going to be something you heard at the supermarket. It's going to be something you felt when you were going for a walk.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What other influences make their way into your writing?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have two nieces and a nephew. When they were much younger, their presence in my life had an interesting effect on my writing. I took care of them a lot, and it gave me a sense of the world of children. It was wonderful. As they get older, I see myself writing books for older children.

It has always been important in my books that the adults can be even a little emotionally neglectful or just living their lives, but in the end there is a safety net with them. In a wonderfully healthy adolescence and teen world, your parents are there — they're supportive, they're loving, they're not too obnoxious — and you go on about your life. When you're home, you're secure and they're there and they leave you alone and then you go out again. I had a huge safety net in my parents as a teenager.

Every book has pieces from my life. For instance, all my nieces and nephews are biracial. I have gay friends who have children. I had a friend whose child ran away. I take looks around me. Another example is that a female friend of mine died, and one of her children kept thinking she saw her, as a ghost out in the garden. There are so many things that I've incorporated in my books. Obviously, these are subjects that I care about and are important.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to talk with students about?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I always ask if any of them journal. I find journaling is a touchstone. When kids do that, they are secure in their writing. There are kids who, as far as they're concerned, writing stops when they leave the school. But, there are kids who are putting down any feelings they have; they're raging on paper. I say not everyone is going to be a writer, but everyone can write. No one ever has to see what they've written.

I tell them "We're not all going to be published, but your emotions — all of you have such strong emotions! Start journaling and become comfortable with what you feel. Write it down and remember. If nothing else, when you're 40 you can laugh about it like I do when I look back at mine."

TEACHINGBOOKS: What sorts of things happen when young people write-?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I'm amazed by teen poets — the poetry slams are just amazing. I am in love with the idea of teenagers getting up there and just going for it. The kids who are participating in poetry slams are the ones with something deep about them, and in recent years, now have this incredible outlet.

When I was in school, if there were some guys who were poets, I didn't know it. Now you're seeing these young men who are. I love that they're being handed the power to do something positive.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Have you ever run up against censorship of your books?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have been asked not to come on author visits. I don't know that I have been banned.

One private religious school asked me not to come because in Toning the Sweep I talk about lynching — not graphically, of course, but I do talk about lynching. Even though I was going to speak to their elementary-aged children, who were too young to have read the book, they said, "We just need to know that you will not mention that book." I said, "No, I'm sorry, I can't do that." So they asked me not to come.

Last year in Michigan, I was speaking to a library reading club, and a couple days before I came, the aide associated with the club decided to call the parents and tell them that in The First Part Last, which was one of the books that the kids were reading, I had "language." She made calls to the library board, she called the parents, and she got nothing. Everyone felt the book was age-appropriate — what kids don't speak like this?

The reasons for banning books are just ludicrous to me. It's interesting to me that the last thing that is banned is always violence. Sexuality, language and content are banned. Violence is not. You can blow up a few buildings, and you can have people dragged down the street. People will stick guns in their children's hands and send them out in the woods to shoot animals, but they don't want to hear about sex. It's so ridiculous.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe your writing process.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I like to write longhand on legal pads. I just stick my legal pad in my backpack and go down to the park. Nowadays, everybody's in the coffeehouses on their laptops. That really freaks me out. I just started with a computer a couple years ago, but I think I'll always have the legal pads with me as well.

I lost the first half of Toning the Sweep on a word processor with no hard drive in it. It was before I understood about hard copies. I lived in a neighborhood next to an elementary school that always used to blow the electricity. At least twice a day the electricity on the whole street would go out. And there I was, page 47, I remember it vividly, had not printed anything. Everything was saved on a disk. I didn't push the little "s." The electricity went out, and it was all gone.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to write in such a wide variety of formats (picture books, poetry, novels)?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I lucked out in the beginning of my career with my editor, Richard Jackson. He never told me that I had to make choices. He never said, "You write picture books." There was never a time when he said, "You can't write poetry or short stories." I have a collection of short stories. I wrote board books. Anything I wrote, he said, "Okay."

Then, I started meeting other writers and saw that there are people who just write novels. I know I sound naïve, but I was surprised that they just write novels or they just write picture books or they just write poetry. I thought it was a given to write whatever I felt like, and I thought everyone did it. There are no parameters for me, which is wonderful. The only thing I won't touch is adult literature. But as far as kids' stuff is concerned, preschool to teen and all forms in between are great.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you believe is the importance of writing books with African-American protagonists?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I can equate it to the first time I was in school and I picked up a book by Ezra Jack Keats. I opened a book and there were children who looked like me. I cannot tell you the world that opened up. When I was a child, Ezra Jack Keats' books were the only ones with African American children in them.

What he was doing was looking out his window and these were the children he was seeing. It doesn't matter that he was white. There was a little girl in a tiny library in Ohio — me — who opened up this book and saw someone who had my skin color.

In all my books, though the stories are universal, the protagonist will likely be an African-American child, because I remember that feeling of being in a sea of books where no one looked like me. My textbooks did not have any African American children. Finally in the '70s I started to see books with African-American child protagonists, including the book Cornbread, Earl and Me.

Even though I want this to be a universal experience, I love the idea that there is an African-American child saying, "This belongs to me. Someone has recognized that kids who look like me are important and valid."

I've gone to schools that were mostly white, and I've had children ask me, "Why do you just write books with black children?" I say, "I'm African American, and I'm writing through my eyes." And then I say, "When you go into your library, how many books do you pick up that have kids who look just like you?" And they always say, "Yeah, there are a lot of them, aren't there?" Then I say, "Don't you think you need a few more like these, too?" And they say, "Yeah, okay."

TEACHINGBOOKS: Despite an emphasis on African-American characters, the themes and emotional journeys in your books strike a universal chord.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe we're all connected. One of the big problems in this country is people don't always feel that they are connected. We're all on this road together, bumping into each other, and we're all so connected. We have been thrown in this place. There has to come a time where we say, "It doesn't really matter if he's black or if he's Asian or if he's white. This is a universal story."

In the end what I want is for anyone to be able to pick up one of these books and it doesn't matter: the color of the children, where they live. All of these stories are everyone's story. If anyone can pick my book up and say, "Yes, this is just a wonderful story; I've felt this; I knew someone who felt this," then I've done what I was supposed to do. What else is there? It's great. It's better than ice cream.

Angela Johnson

In-depth Written Interview

Insights Beyond the Slideshows

Angela Johnson interviewed while in Madison, Wisconsin on October 6, 2005.TEACHINGBOOKS: You've won the Coretta Scott King Author Award three times — for Toning the Sweep, Heaven and The First Part Last. Your book, Heaven was written before The First Part Last but is a sort of prequel to it. How did you come to write The First Part Last after having already written Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: The wonderful thing about The First Part Last is I didn't want to write the book at all. As far as I'm concerned, I don't do prequels; I don't do sequels.

Then, I went to New York and visited some after-school programs for a week. I was on the subway and there was this beautiful kid. He looked about 15 or 16, and he was with a baby. It was 11:00 in the morning, and I was thinking, "Why is this kid not in school? Is this his daughter; is this his sister? What's the deal?"

The train stopped, and he got ready to get off the train, I actually wanted to follow this kid down the street and question him. Something came over me. I went back to the hotel and wrote three chapters of what became The First Part Last. I felt provoked, and I didn't want it to happen. Sometimes it just comes over you and there is the story or the character. The First Part Last was the easiest book I've ever written. Bobby was just there. Everything was there.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The First Part Last, like many of your books, carries some heavy messages, though your writing never comes off as preachy.

ANGELA JOHNSON: Preaching to teens about teenage pregnancy is like preaching to a lamp. These are human beings, and they do what they want.

The First Part Last is definitely a cautionary tale, but it's not preachy. Bobby loves his baby, but what has he lost? He's lost the love of his life at 16. He's lost many of his freedoms. His friends still love him, but he's lost part of that relationship. He's lost being a child, because he is now the daddy. I always figure, show what's real — you don't have to preach. I love Bobby's responsibility. He has almost a romantic belief that, "I've lost Nia, so I'm going to raise this baby." It's noble. But then reality sets in, and some of it is not pretty.

The majority of parents have said they like The First Part Last. But, I have had parents say, "I'm not letting my kid read this book because it'll give them ideas." I said, "Ideas about going into a coma? Ideas about having this baby who's weighed you down and you've lost your childhood?" I mean, which idea? Obviously these people haven't read the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Will you write about any other characters from Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: Yes. One more book — it's called Sweet. It's about Shoogy. Shoogy is still unknowable to me. I'm writing about her, and yet I still don't really know her. She is an enigma.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also write and have written many picture books. Where did your idea for A Sweet Smell of Roses emerge from?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I based the two little girls in A Sweet Smell of Roses on two real little girls who had marvelous spirit and participated in civil rights marches. In the documentary called Eyes on the Prize, two women were interviewed who were around seven and eight during the civil rights movement. They shared their experiences about how they would go off to marches without their parents. The wonderful thing is, the adults around them took care of them as if they were their own children.

Something really interesting happened in the creation of A Sweet Smell of Roses. In creating picture books, there's usually little or no collaboration between author and artist. The illustrator, Eric Velasquez, was selected by my editor; I never did share anything to him about why I wrote the book. Would you believe, Eric included artwork from the Eyes on the Prizedocumentary, and he wrote a foreword for the book about the documentary's filmmaker. It's just this bizarre kismet.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Several of your books don't have happy endings. How do you respond when people point this out?

ANGELA JOHNSON: At the end of some of my books, everything is not always happiness and light. Life is not always this big, jolly party. It is just life, and it just goes on. But I always like to leave the end as a beginning. It's not necessarily happy, and it's not necessarily sad. It is just life. I'm a happy person, but I'm a realist and I write contemporary realism.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also like to include humor in your books.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe there should be more fun books with African-American children in them. We're inundated with family stories and folk tales and the happy family. I understand that; I write those books, too. But there has to be a place for humor.

I love humor in any way, shape or form. Where Have You Gone, Vivian Dartow is going to be my funny book. Writing this book, I relived high school all over again — I thought I had it down, and in reality, I was just the biggest nerd.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you're stuck?

ANGELA JOHNSON: When I have trouble writing, I do everything but write. I like to travel when I'm blocked, and I usually come out of writing blocks after I travel.

As it turns out, my books are usually geographically motivated. I wrote A Cool Moonlightwhen I was in Aruba. I was on a beach with lots of sunlight writing a book about a child who can't go out in the daylight. I had just come back from Cape Cod when I wrote Looking for Red. The First Part Last came from New York, and Toning the Sweep came from when I was in the desert with my brother. Bird is the one book that was written when I was loving being at home.

There's always going to be something in life that will ignite you. I always believe that. It's going to be a newspaper article. It's going to be something you heard at the supermarket. It's going to be something you felt when you were going for a walk.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What other influences make their way into your writing?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have two nieces and a nephew. When they were much younger, their presence in my life had an interesting effect on my writing. I took care of them a lot, and it gave me a sense of the world of children. It was wonderful. As they get older, I see myself writing books for older children.

It has always been important in my books that the adults can be even a little emotionally neglectful or just living their lives, but in the end there is a safety net with them. In a wonderfully healthy adolescence and teen world, your parents are there — they're supportive, they're loving, they're not too obnoxious — and you go on about your life. When you're home, you're secure and they're there and they leave you alone and then you go out again. I had a huge safety net in my parents as a teenager.

Every book has pieces from my life. For instance, all my nieces and nephews are biracial. I have gay friends who have children. I had a friend whose child ran away. I take looks around me. Another example is that a female friend of mine died, and one of her children kept thinking she saw her, as a ghost out in the garden. There are so many things that I've incorporated in my books. Obviously, these are subjects that I care about and are important.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to talk with students about?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I always ask if any of them journal. I find journaling is a touchstone. When kids do that, they are secure in their writing. There are kids who, as far as they're concerned, writing stops when they leave the school. But, there are kids who are putting down any feelings they have; they're raging on paper. I say not everyone is going to be a writer, but everyone can write. No one ever has to see what they've written.

I tell them "We're not all going to be published, but your emotions — all of you have such strong emotions! Start journaling and become comfortable with what you feel. Write it down and remember. If nothing else, when you're 40 you can laugh about it like I do when I look back at mine."

TEACHINGBOOKS: What sorts of things happen when young people write-?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I'm amazed by teen poets — the poetry slams are just amazing. I am in love with the idea of teenagers getting up there and just going for it. The kids who are participating in poetry slams are the ones with something deep about them, and in recent years, now have this incredible outlet.

When I was in school, if there were some guys who were poets, I didn't know it. Now you're seeing these young men who are. I love that they're being handed the power to do something positive.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Have you ever run up against censorship of your books?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have been asked not to come on author visits. I don't know that I have been banned.

One private religious school asked me not to come because in Toning the Sweep I talk about lynching — not graphically, of course, but I do talk about lynching. Even though I was going to speak to their elementary-aged children, who were too young to have read the book, they said, "We just need to know that you will not mention that book." I said, "No, I'm sorry, I can't do that." So they asked me not to come.

Last year in Michigan, I was speaking to a library reading club, and a couple days before I came, the aide associated with the club decided to call the parents and tell them that in The First Part Last, which was one of the books that the kids were reading, I had "language." She made calls to the library board, she called the parents, and she got nothing. Everyone felt the book was age-appropriate — what kids don't speak like this?

The reasons for banning books are just ludicrous to me. It's interesting to me that the last thing that is banned is always violence. Sexuality, language and content are banned. Violence is not. You can blow up a few buildings, and you can have people dragged down the street. People will stick guns in their children's hands and send them out in the woods to shoot animals, but they don't want to hear about sex. It's so ridiculous.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe your writing process.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I like to write longhand on legal pads. I just stick my legal pad in my backpack and go down to the park. Nowadays, everybody's in the coffeehouses on their laptops. That really freaks me out. I just started with a computer a couple years ago, but I think I'll always have the legal pads with me as well.

I lost the first half of Toning the Sweep on a word processor with no hard drive in it. It was before I understood about hard copies. I lived in a neighborhood next to an elementary school that always used to blow the electricity. At least twice a day the electricity on the whole street would go out. And there I was, page 47, I remember it vividly, had not printed anything. Everything was saved on a disk. I didn't push the little "s." The electricity went out, and it was all gone.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to write in such a wide variety of formats (picture books, poetry, novels)?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I lucked out in the beginning of my career with my editor, Richard Jackson. He never told me that I had to make choices. He never said, "You write picture books." There was never a time when he said, "You can't write poetry or short stories." I have a collection of short stories. I wrote board books. Anything I wrote, he said, "Okay."

Then, I started meeting other writers and saw that there are people who just write novels. I know I sound naïve, but I was surprised that they just write novels or they just write picture books or they just write poetry. I thought it was a given to write whatever I felt like, and I thought everyone did it. There are no parameters for me, which is wonderful. The only thing I won't touch is adult literature. But as far as kids' stuff is concerned, preschool to teen and all forms in between are great.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you believe is the importance of writing books with African-American protagonists?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I can equate it to the first time I was in school and I picked up a book by Ezra Jack Keats. I opened a book and there were children who looked like me. I cannot tell you the world that opened up. When I was a child, Ezra Jack Keats' books were the only ones with African American children in them.

What he was doing was looking out his window and these were the children he was seeing. It doesn't matter that he was white. There was a little girl in a tiny library in Ohio — me — who opened up this book and saw someone who had my skin color.

In all my books, though the stories are universal, the protagonist will likely be an African-American child, because I remember that feeling of being in a sea of books where no one looked like me. My textbooks did not have any African American children. Finally in the '70s I started to see books with African-American child protagonists, including the book Cornbread, Earl and Me.

Even though I want this to be a universal experience, I love the idea that there is an African-American child saying, "This belongs to me. Someone has recognized that kids who look like me are important and valid."

I've gone to schools that were mostly white, and I've had children ask me, "Why do you just write books with black children?" I say, "I'm African American, and I'm writing through my eyes." And then I say, "When you go into your library, how many books do you pick up that have kids who look just like you?" And they always say, "Yeah, there are a lot of them, aren't there?" Then I say, "Don't you think you need a few more like these, too?" And they say, "Yeah, okay."

TEACHINGBOOKS: Despite an emphasis on African-American characters, the themes and emotional journeys in your books strike a universal chord.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe we're all connected. One of the big problems in this country is people don't always feel that they are connected. We're all on this road together, bumping into each other, and we're all so connected. We have been thrown in this place. There has to come a time where we say, "It doesn't really matter if he's black or if he's Asian or if he's white. This is a universal story."

In the end what I want is for anyone to be able to pick up one of these books and it doesn't matter: the color of the children, where they live. All of these stories are everyone's story. If anyone can pick my book up and say, "Yes, this is just a wonderful story; I've felt this; I knew someone who felt this," then I've done what I was supposed to do. What else is there? It's great. It's better than ice cream.

The First Part Last Discussion Questions

AGENDA:

Review questions from last class.

Discuss possible projects/

Discussion Questions

Review questions from last class.

Discuss possible projects/

Discussion Questions

- Parts I & II

- Who are the main characters?

- Who is the Narrator?

- What is this book about?

- When and Where does this story take place?

- What do you think about the author's use of language?

Is the language realistic for Bobby? - Discuss the writing style of this book (non-linear): Now/Then.

Do you like it?

Does it make it harder to read?

Why do you think the author decided to write it this way? - How does Bobby feel about his baby?

- How does Bobby feel about Nia?

- Where do you think Nia is? Why isn't she taking care of her baby?

- Talk about parents' and friends' reactions to news of the pregnancy?

- Do you think Bobby is a good kid?

- What do you think about this book so far?

- Read pages 58 - 61 and pages 70 - 75 together.

- What happened?

Why did Bobby get arrested? - What was the consequence of Bobby taking the day off? (page 95)

- What decision had Bobby & Nia mad about the baby? (page 106) Why?

- What happens for the first time on page 115?

- Where is Nia?

- What happened to her?

- What did Bobby decide to do? (page 118) Why? (page 125)

- Why is the baby's name Feather? (page 124)

- Where do Bobby and Feather end up?

- What do you think will happen? Happily ever after?

- What did you think about this book?

Parts III & IV

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Montana 1948 Readings/Natalie Goldberg Test 1 "I remember"

Montana 1948 Readings/Natalie Goldberg Test 1 "I remember" Marcy Gamzon • Sep 21 (Edited Sep 21) 100 points Due Tomorrow AGENDA:...

-

AGENDA 1, For classwork credit: Read the following two stories by Sandra Cisneros. Then discuss the questions for Barbie-Q with a p...

-

Choose ONE of the following topics and discuss it in a well-developed essay. You may use your book to provide text-based details. Post yo...

-

In James Longenbach’s “The Art of the Poetic Line,” he mentions three kinds of line endings: End stopped lines end with punctuation, as ...