AGENDA:

Happy Halloween! Explore Halloween poems.

www.poets.org/poetsorg/halloween-poems

http://academyofamericanpoets.cmail19.com/t/ViewEmail/y/1A7DDDF6757048EF/FF0EB04BBFA2CA21A2432AF2E34A2A5F

WRITING PROMPT:

Write a poem for Halloween or Autumn. Read Keats "Ode to Autumn".

www.poetryfoundation.org/resources/learning/core-poems/detail/44484

HMWK: Finish Mango Street for Friday. Complete at least 5 vignettes to pass in for marking period grade.

Test on House on Mango Street

This course will serve as an introduction to the basic grammatical rules of standard written English through the use of writing exercises and creative activities. Students will review basic grammar and move on to more advanced stylistic concerns essential to creative writers in all genres. 2nd semester--writing for self-discovery

Monday, October 31, 2016

Thursday, October 27, 2016

House on Mango Street books

AGENDA:

WRITING: Work on your "House on..." books.

1. Design a cover and cover page

2. Include a table of contents--the order of your vignettes (don't worry about page numbers)

3. Put the vignettes in order. Add pictures as appropriate.

4. Last page should be your "About the Author" blurb (and a picture of you)

WRITING: Work on your "House on..." books.

1. Design a cover and cover page

2. Include a table of contents--the order of your vignettes (don't worry about page numbers)

3. Put the vignettes in order. Add pictures as appropriate.

4. Last page should be your "About the Author" blurb (and a picture of you)

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

House on Mango Street

AGENDA:

Check out Shmoop:

http://www.shmoop.com/house-on-mango-street/

http://www.enotes.com/topics/house-on-mango-street

2. READING/DISCUSSION: Read "Eleven" and "Barbie-Q" posted below

3. WRITING: Begin your House on My Street vignette book

The House on Mango Street is a deceptive work. It is a book of short stories—and sometimes not even full stories, but character sketches and vignettes—that add up, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "to tell one big story, each story contributing to the whole—like beads in a necklace." That story is told in language that seems simple but that possesses the associative richness of poetry, and whose slang and breaks from grammatical correctness contribute to its immediacy. It is narrated in the voice of a young girl—a girl too young to know that no one may ever hear her—but whose voice is completely convincing, because it is the creation of a mature and sophisticated writer. For example, The House on Mango Street appears to wander casually from subject to subject—from hair to hips, from clouds to feet, from an invalid aunt to a girl named Sally, who has "eyes like Egypt" and whose father sometimes beats her. But this apparent randomness disguises an artful exploration of themes of individual identity and communal loyalty, estrangement and loss, escape and return, the lure of romance and the dead end of sexual inequality and oppression.

The House on Mango Street is also a book about a culture—that of Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans—that has long been veiled by demeaning stereotypes and afflicted by internal ambivalence. In some ways it resembles the immigrant cultures that your students may have encountered in books like My Ántonia, The Jungle, and Call It Sleep. But unlike Americans of Slavic or Jewish ancestry, Chicanos have been systematically excluded from the American mainstream in ways that suggest the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Although Cisneros uses language as a recurring metaphor for the gulf between Mexican-Americans and the majority culture, what keeps Esperanza Cordero and her family and friends locked in their barrio is something more obdurate than language: a confluence of racism, poverty, and shame. It may help your discussion to remind students that the ancestors of many Chicanos did not come to the United States by choice, but simply found themselves in alien territory as a result of the U.S.'s expansionist policy into country that had once been Mexican.

But although The House on Mango Street will have a particularly strong appeal to Latino students, who may never have encountered a book that speaks so pointedly to their own experience, it is a work that captures the universal pangs of otherness—what Cisneros, in her introduction to the tenth anniversary edition (published by Knopf, $18.00), has called "the shame of being poor, of being female, of being not-quite-good-enough." It suggests from where that otherness comes and shows how it can become a cause for celebration rather than shame. Few students, regardless of their ancestry or gender, will come away from this book without a strong sensation of having glimpsed a secret part of themselves. For, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "You, the reader, are Esperanza.... You cannot forget who you are."

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. She has worked as a teacher to high school dropouts, a poet-in-the-schools, a college recruiter, and an arts administrator. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, and the recipient of numerous awards, Cisneros is also the author of Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories, My Wicked Wicked Ways, and Loose Woman. The daughter of a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother, and sister to six brothers, she is nobody's mother and nobody's wife. She lives in San Antonio, Texas, and is currently at work on a novel.

HMWK: Read to pg.48 in House on Mango Street

Eleven

From Woman Hollering Creek Copyright © 1991 by Sandra Cisneros. Reprinted by permission of Susan Bergholtz Literary Services, New York. All rights reserved.

Discussion questions for Sandra Cisneros‘s “Barbie-Q”

Check out Shmoop:

http://www.shmoop.com/house-on-mango-street/

http://www.enotes.com/topics/house-on-mango-street

EQ: What are the qualities of a poetic vignette?

2. READING/DISCUSSION: Read "Eleven" and "Barbie-Q" posted below

3. WRITING: Begin your House on My Street vignette book

The House on Mango Street is a deceptive work. It is a book of short stories—and sometimes not even full stories, but character sketches and vignettes—that add up, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "to tell one big story, each story contributing to the whole—like beads in a necklace." That story is told in language that seems simple but that possesses the associative richness of poetry, and whose slang and breaks from grammatical correctness contribute to its immediacy. It is narrated in the voice of a young girl—a girl too young to know that no one may ever hear her—but whose voice is completely convincing, because it is the creation of a mature and sophisticated writer. For example, The House on Mango Street appears to wander casually from subject to subject—from hair to hips, from clouds to feet, from an invalid aunt to a girl named Sally, who has "eyes like Egypt" and whose father sometimes beats her. But this apparent randomness disguises an artful exploration of themes of individual identity and communal loyalty, estrangement and loss, escape and return, the lure of romance and the dead end of sexual inequality and oppression.

The House on Mango Street is also a book about a culture—that of Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans—that has long been veiled by demeaning stereotypes and afflicted by internal ambivalence. In some ways it resembles the immigrant cultures that your students may have encountered in books like My Ántonia, The Jungle, and Call It Sleep. But unlike Americans of Slavic or Jewish ancestry, Chicanos have been systematically excluded from the American mainstream in ways that suggest the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. Although Cisneros uses language as a recurring metaphor for the gulf between Mexican-Americans and the majority culture, what keeps Esperanza Cordero and her family and friends locked in their barrio is something more obdurate than language: a confluence of racism, poverty, and shame. It may help your discussion to remind students that the ancestors of many Chicanos did not come to the United States by choice, but simply found themselves in alien territory as a result of the U.S.'s expansionist policy into country that had once been Mexican.

But although The House on Mango Street will have a particularly strong appeal to Latino students, who may never have encountered a book that speaks so pointedly to their own experience, it is a work that captures the universal pangs of otherness—what Cisneros, in her introduction to the tenth anniversary edition (published by Knopf, $18.00), has called "the shame of being poor, of being female, of being not-quite-good-enough." It suggests from where that otherness comes and shows how it can become a cause for celebration rather than shame. Few students, regardless of their ancestry or gender, will come away from this book without a strong sensation of having glimpsed a secret part of themselves. For, as Sandra Cisneros has written, "You, the reader, are Esperanza.... You cannot forget who you are."

ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

Sandra Cisneros was born in Chicago in 1954. She has worked as a teacher to high school dropouts, a poet-in-the-schools, a college recruiter, and an arts administrator. Internationally acclaimed for her poetry and fiction, and the recipient of numerous awards, Cisneros is also the author of Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories, My Wicked Wicked Ways, and Loose Woman. The daughter of a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother, and sister to six brothers, she is nobody's mother and nobody's wife. She lives in San Antonio, Texas, and is currently at work on a novel.

HMWK: Read to pg.48 in House on Mango Street

Eleven

By Sandra Cisneros

What they don’t understand about birthdays and what they never tell you is that when you’re eleven, you’re also ten, and nine, and eight, and seven, and six, and five, and four, and three, and two, and one. And when you wake up on your eleventh birthday you expect to feel eleven, but you don’t. You open your eyes and everything’s just like yesterday, only it’s today. And you don’t feel eleven at all. You feel like you’re still ten. And you are—underneath the year that makes you eleven.

Like some days you might say something stupid, and that’s the part of you that’s still ten. Or maybe some days you might need to sit on your mama’s lap because you’re scared, and that’s the part of you that’s five. And maybe one day when you’re all grown up maybe you will need to cry like if you’re three, and that’s okay. That’s what I tell Mama when she’s sad and needs to cry. Maybe she’s feeling three.

Because the way you grow old is kind of like an onion or like the rings inside a tree trunk or like my little wooden dolls that fit one inside the other, each year inside the next one. That’s how being eleven years old is.

You don’t feel eleven. Not right away. It takes a few days, weeks even, sometimes even months before you say Eleven when they ask you. And you don’t feel smart eleven, not until you’re almost twelve. That’s the way it is.

Only today I wish I didn’t have only eleven years rattling inside me like pennies in a tin Band-Aid box. Today I wish I was one hundred and two instead of eleven because if I was one hundred and two I’d have known what to say when Mrs. Price put the red sweater on my desk. I would’ve known how to tell her it wasn’t mine instead of just sitting there with that look on my face and nothing coming out of my mouth.

“Whose is this?” Mrs. Price says, and she holds the red sweater up in the air for all the class to see. “Whose? It’s been sitting in the coatroom for a month.”

“Not mine,” says everybody. “Not me.”

“It has to belong to somebody,” Mrs. Price keeps saying, but nobody can remember. It’s an ugly sweater with red plastic buttons and a collar and sleeves all stretched out like you could use it for a jump rope. It’s maybe a thousand years old and even if it belonged to me I wouldn’t say so.

Maybe because I’m skinny, maybe because she doesn’t like me, that stupid Sylvia Saldivar says, “I think it belongs to Rachel.” An ugly sweater like that, all raggedy and old, but Mrs. Price believes her. Mrs. Price takes the sweater and puts it right on my desk, but when I open my mouth nothing comes out.

“That’s not, I don’t, you’re not . . . Not mine,” I finally say in a little voice that was maybe me when I was four.

“Of course it’s yours,” Mrs. Price says, “I remember you wearing it once.” Because she’s older and the teacher, she’s right and I’m not.

Not mine, not mine, not mine, but Mrs. Price is already turning to page thirty-two, and math problem number four. I don’t know why but all of a sudden I’m feeling sick inside, like the part of me that’s three wants to come out of my eyes, only I squeeze them shut tight and bite down on my teeth real hard and try to remember today I am eleven, eleven. Mama is making a cake for me for tonight, and when Papa comes home everybody will sing Happy birthday, happy birthday to you.

But when the sick feeling goes away and I open my eyes, the red sweater’s still sitting there like a big red mountain. I move the red sweater to the corner of my desk with my ruler. I move my pencil and books and eraser as far from it as possible. I even move my chair a little to the right. Not mine, not mine, not mine.

In my head I’m thinking how long till lunchtime, how long till I can take the red sweater and throw it over the schoolyard fence, or leave it hanging on a parking meter, or bunch it up into a little ball and toss it in the alley. Except when math period ends Mrs. Price says loud and in front of everybody, “Now, Rachel, that’s enough,” because she sees I’ve shoved the red sweater to the tippy-tip corner of my desk and it’s hanging all over the edge like a waterfall, but I don’t care.

“Rachel,” Mrs. Price says. She says it like she’s getting mad. “You put that sweater on right now and no more nonsense.”

“But it’s not—“

“Now!” Mrs. Price says.

This is when I wish I wasn’t eleven, because all the years inside of me—ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one—are pushing at the back of my eyes when I put one arm through one sleeve of the sweater that smells like cottage cheese, and then the other arm through the other and stand there with my arms apart like if the sweater hurts me and it does, all itchy and full of germs that aren’t mine.

That’s when everything I’ve been holding in since this morning, since when Mrs. Price put the sweater on my desk, finally lets go, and all of a sudden I’m crying in front of everybody. I wish I was invisible but I’m not. I’m eleven and it’s my birthday today and I’m crying like I’m three in front of everybody. I put my head down on the desk and bury my face in my stupid clown-sweater arms. My face all hot and spit coming out of my mouth because I can’t stop the little animal noises from coming out of me, until there aren’t any more tears left in my eyes, and it’s just my body shaking like when you have the hiccups, and my whole head hurts like when you drink milk too fast.

But the worst part is right before the bell rings for lunch. That stupid Phyllis Lopez, who is even dumber than Sylvia Saldivar, says she remembers the red sweater is hers! I take it off right away and give it to her, only Mrs. Price pretends like everything’s okay.

Today I’m eleven. There’s a cake Mama’s making for tonight, and when Papa comes home from work we’ll eat it. There’ll be candles and presents and everybody will sing Happy birthday, happy birthday to you, Rachel, only it’s too late.

I’m eleven today. I’m eleven, ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one, but I wish I was one hundred and two. I wish I was anything but eleven, because I want today to be far away already, far away like a runaway balloon, like a tiny o in the sky, so tiny-tiny you have to close your eyes to see it.

From Woman Hollering Creek Copyright © 1991 by Sandra Cisneros. Reprinted by permission of Susan Bergholtz Literary Services, New York. All rights reserved.

Barbie-Q

By Sandra Cisneros

Yours is the one with mean eyes and a ponytail. Striped swimsuit, stilettos, sunglasses, and gold hoop earrings. Mine is the one with bubble hair. Red swimsuit, stilettos, pearl earrings, and a wire stand. But that’s all we can afford, besides one extra outfit apiece. Yours, “Red Flair,” sophisticated A-line coatdress with a Jackie Kennedy pillbox hat, white gloves, handbag, and heels included. Mine, “solo in the Spotlight,” evening elegance in black glitter strapless gown with a puffy skirt at the bottom like a mermaid tail, formal-length gloves, pink chiffon scarf, and mike included. From so much dressing and undressing, the black glitter wears off where her titties stick out. This and a dress invented from an old sock when we cut holes here and here and here, the cuff rolled over for the glamorous, fancy-free, off-the-shoulder look.

Every time the same story. Your Barbie is roommates with my Barbie, and my Barbie’s boyfriend comes over and your Barbie steals him, okay? Kiss kiss kiss. Then the two Barbies fight. You dumbbell! He’s mine. Oh no he’s not, you stinky! Only Ken’s invisible, right? Because we don’t have money for a stupid-looking boy doll when we’d both rather ask for a new Barbie outfit next Christmas. We have to make do with your mean-eyed Barbie and my bubblehead Barbie and our one outfit apiece not including the sock dress.

Until next Sunday when we are walking through the flea market on Maxwell Street and there! Lying on the street next to some tool bits, and platform shoes with the heels all squashed, and a fluorescent green wicker wastebasket, and aluminum foil, and hubcaps, and a pink shag rug, and windshield wiper blades, and dusty mason jars, and a coffee can full of rusty nails. There! Where? Two Mattel boxes. One with the “Career Gal” ensemble, snappy black-and-white business suit, three-quarter-length sleeve jacket with kick-pleated skirt, red sleeveless shell, gloves, pumps, and matching hat included. The other, “Sweet Dreams,” dreamy pink-and-white plaid nightgown and matching robe, lace-trimmed slippers, hair-brush and hand mirror included. How much? Please, please, please, please, please, please, please, until they say okay.

On the outside you and me skipping and humming but inside we are doing loopity-loops and pirouetting. Until at the next vendor’s stand, next to boxed pies, and bright orange toilet brushes, and rubber gloves, and wrench sets, and bouquests of feather flowers, and glass towel racks, and steel wool, and Alvin and the Chipmunks records, there! And there! And there! And there! and there! and there! and there! Bendable Legs Barbie with her new page-boy hairdo, Midge, Barbie’s best friend. Ken, Barbie’s boyfriend. Skipper, Barbie’s little sister. Tutti and Todd, Barbie and Skipper’s tiny twin sister and brother. Skipper’s friends, Scooter and Ricky. Alan, Ken’s buddy. And Francie, Barbie’ MOD’ern cousin.

Everybody today selling toys, all of them damaged with water and smelling of smoke. Because a big toy warehouse on Halsted Street burned down yesterday—see there?—the smoke still rising and drifting across the Dan Ryan expressway. And now there is a big fire sale at Maxwell Street, today only.

So what if we didn’t get our new Bendable Legs Barbie and Midge and Ken and Skipper and Tutti and Todd and Scooter and Ricky and Alan and Francie in nice clean boxes and had to buy them on Maxwell Street, all water-soaked and sooty. So what if our Barbies smell like smoke when you hold them up to your nose even after you wash and wash and wash them. And if the prettiest doll, Barbie’s MOD’ern cousin Francie with real eyelashes, eyelash brush included, has a left foot that’s melted a little—so? If you dress her in her new “Prom Pinks” outfit, satin splendor with matching coat, gold belt, clutch, and hair bow included, so long as you don’t lift her dress, right?—who’s to know.

Discussion questions for Sandra Cisneros‘s “Barbie-Q”

- What could Barbie’s wardrobe, e.g. Red Flair, Career Gal, Jackie Kennedy pillbox hat, Prom Pinks, suggest about a woman’s status in society?

- What values and ideals does Barbie represent/symbolize in the story? What does she offer the two girls in the story?

- Do you believe that Cisneros has some feminist concerns in Barbie-Q? If yes, explain what these concerns could be.

- What could the image of flawed/damaged dolls signify?

- Do you believe that Cisneros voices some racial concerns in Barbie-Q? If yes, explain what these concerns could be. Comment on the origin of the protagonists.

- What could the story tell us about the influence of hegemonic culture over the dominated?

- Discuss whether Barbie is the embodiment of women’s oppression or liberation.

- Why does Cisneros associate the title of the story with a cooking technique?

Continue to work on writing your own "House on Mango Street"

8-10 Vignettes modeled on the book but based on your own life, family, friends, neighborhood

Title your vignettes

8-10 Vignettes modeled on the book but based on your own life, family, friends, neighborhood

Title your vignettes

Friday, October 21, 2016

Comma Rules

| Rule No. 1: In a simple series, use a comma to separate the elements, but don’t put a comma before the conjunction. | Rule No. 2: Use a comma to separate two independent clauses connected by a coordinating conjunction. |

| Rule No. 3: Use a comma following an introductory clause or prepositional phrase of four words or more. | Rule No. 4: Use commas to set off modifiers that are not essential to the reader's ability to identify a particular person, place or thing. |

| Rule No. 5: Use commas to separate adjectives of equal rank. | Rule No. 6: Use commas to set off words that add emphasis, shift attention or provide a fuller explanation (parentheticals, "yes," "no," names in direct address). |

| Rule No. 7: Use commas to set off participial modifiers that come at the beginning of a sentence or after the verb. | Rule No. 8: Use a comma, carefully, to set off quotes or paraphrases. |

| Rule No. 9: Use a comma with hometowns, ages, years with months and days, names of states and nations with cities, affiliations and most large numbers. | Rule No. 10: Use a comma to separate duplicate words to eliminate confusion. |

Thursday, October 13, 2016

House on Mango Street

Finish First Part Last PROJECTS for presentation!

House on Mango Street--Vignettes

2. Introduction to The House on Mango Street

Go to library and pick up book

EQ: What is a vignette?

AGENDA:

1, Finish up First Part Last projects for presentation Monday. Finish animated poetry.

2. Introduction to The House on Mango Street

Go to library and pick up book

EQ: What is a vignette?

vi·gnette

vinˈyet/

noun

noun: vignette; plural noun: vignettes

- 1.a brief evocative description, account, or episode.

- 2.a small illustration or portrait photograph that fades into its background without a definite border.

- a small ornamental design filling a space in a book or carving, typically based on foliage.

verb

verb: vignette; 3rd person present: vignettes; past tense: vignetted; past participle:vignetted; gerund or present participle: vignetting

1.

Four Skinny Trees

"Four Skinny Trees" is an excerpt from the book by Sandra Cisneros entitled The House on Mango Street. "Four Skinny Trees" is found on pages 74 and 75. Copyright Sandra Cisneros, 1984 and published by Vintage Contemporaries, 1991.

"They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn't appreciate these things.

"Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

"Let one forget his reason for being, they'd all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

"When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete. Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be."

"They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn't appreciate these things.

"Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

"Let one forget his reason for being, they'd all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

"When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete. Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be."

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

First Part/Last

Agenda:

- Parts III & IV

- Read pages 58 - 61 and pages 70 - 75 together.

- What happened?

Why did Bobby get arrested? - What was the consequence of Bobby taking the day off? (page 95)

- What decision had Bobby & Nia mad about the baby? (page 106) Why?

- What happens for the first time on page 115?

- Where is Nia?

- What happened to her?

- What did Bobby decide to do? (page 118) Why? (page 125)

- Why is the baby's name Feather? (page 124)

- Where do Bobby and Feather end up?

- What do you think will happen? Happily ever after?

- What did you think about this book?

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

First Part Last Projects

Scholastic Writing Awards

First Part Last Projects

How do you think your life would change as a teenager if you suddenly had the responsibility of an infant? Make a schedule of your life as it is now (look at your day planner) and then make a new one based on a life with baby.

Knowledge:

1. Describe how Bobby and Nia’s parents react to the news of her pregnancy. How would yours?

2. Find a quote that most reveals who Bobby is as a person. Explain why you picked it.

Comprehension:

1. Find three examples that show what kind of father Bobby is to Feather.

2. What do you think is the most difficult thing for Bobby? Why? (Answer this question after a few chapters, answer it again at the end of the novel and see if the answer changes)

Application:

1. Predict what happens to this family ten years into the future. Explain why.

2. Write ten questions you would ask Bobby, Mary, and Nia if you could.

Analyze:

1. On page 35 Bobby says, “ … which pisses her off and makes her scream, and then I look around my room and miss me.” Explain what he means.

2. Angela Johnson tells the story in a non-linear fashion. Why, do you think, she chose this literary device to reveal the story?

Synthesize

1. How would you cope under the extraordinary circumstances that Bobby finds himself?

2. Would you make the same choices?

Evaluation:

1. If Bobby had Nia’s help raising Feather would he be a different father? What makes you think so?

2. Do you agree with Mary and Fred’s approach to grandparenthood? Why or why not?

Multiple Intelligence Projects for

The First Part Last by Angela Johnson

Verbal/ Linguistic

Write at least five letters to Nia explaining what is happening with both Bobby and Feather. Be specific!

or

Study the spare, lyrical writing of Angela Johnson and try to write one scene of a story with a similar quality and the same economy of words.

Logical/ Mathematical:

Find the most recent statistics that you can about teen pregnancy in America. Create at least one graph explaining the results you discovered.

Visual/ Spatial:

Create a piece of art that you feel represents Bobby’s emotions throughout the novel. Think about form, color and line as you create your work. Explain your art in a brief, but illuminating paragraph.

Body/Kinesthetic

In small groups, act out scenes from the novel.

Or-

Write the dialogue and act out the scenes that are left off camera (like what Nia says when she meets Bobby with a balloon on his birthday).

Musical/ Rhythmic

Either create an original piece of music yourself to accompany the story or, find at least three songs that you think belong on the soundtrack of the movie version of this book. Explain why you chose these songs (and include a copy of the lyrics) in a brief journal.

Interpersonal:

Cooperative Learning Project:

In groups of no more than three explore and research one aspect of teen pregnancy (or choose one of your own):

How sex education affects pregnancy rates

Social implications of teen pregnancy on communities

Long-term effects for the mother (and/or father) for future success

Long term success for the infant in health and education

The availability of birth control and other services on pregnancy rates

Which children are most at risk for teen pregnancy

Adoption

Foster care system

Teen shelters

Outstanding programs for young mothers and fathers

Abstinence programs

Then, create a website (or pamphlet) sharing your compilation of facts with the public. Invite the public +/or other teens in a discussion via a message board about it.

Intrapersonal:

Write a letter to yourself about where you want to be in ten years. Reflect on how your goals would be compromised if you were forced to turn your attention to another human being. Assume that your responsibilities would be maximized similar to Bobby’s and that adults would let you assume the brunt of your own mistake.

Refer to the letter as needed.

CREATE a movie trailer for the book using Movie Maker utilizing music and images

First Part Last/Nonlinear narrative

AGENDA:

A frame story (also known as a frame tale or frame narrative) is a literary technique that sometimes serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, whereby an introductory or main narrative is presented, at least in part, for the purpose of setting the stage either for a more emphasized second narrative or for a set of shorter stories. The frame story leads readers from a first story into another, smaller one (or several ones) within it.

Nonlinear narrative, disjointed narrative or disrupted narrative is a narrative technique, sometimes used in literature, film, hypertext websites and other narratives, where events are portrayed, for example out of chronological order, or in other ways where the narrative does not follow the direct causality pattern of the events featured, such as parallel distinctive plot lines, dream immersions or narrating another story inside the main plot-line. It is often used to mimic the structure and recall of human memory, but has been applied for other reasons as well.

In your journal, respond to the following discussion questions:

Discussion Questions

Parts I & II

A frame story (also known as a frame tale or frame narrative) is a literary technique that sometimes serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, whereby an introductory or main narrative is presented, at least in part, for the purpose of setting the stage either for a more emphasized second narrative or for a set of shorter stories. The frame story leads readers from a first story into another, smaller one (or several ones) within it.

Nonlinear narrative, disjointed narrative or disrupted narrative is a narrative technique, sometimes used in literature, film, hypertext websites and other narratives, where events are portrayed, for example out of chronological order, or in other ways where the narrative does not follow the direct causality pattern of the events featured, such as parallel distinctive plot lines, dream immersions or narrating another story inside the main plot-line. It is often used to mimic the structure and recall of human memory, but has been applied for other reasons as well.

In your journal, respond to the following discussion questions:

Discussion Questions

Parts I & II

- Who are the main characters?

- Who is the Narrator?

- What is this book about?

- When and Where does this story take place?

- What do you think about the author's use of language?

Is the language realistic for Bobby? - Discuss the writing style of this book (non-linear): Now/Then.

Do you like it?

Does it make it harder to read?

Why do you think the author decided to write it this way? - How does Bobby feel about his baby?

- How does Bobby feel about Nia?

- Where do you think Nia is? Why isn't she taking care of her baby?

- Talk about parents' and friends' reactions to news of the pregnancy?

- Do you think Bobby is a good kid?

- What do you think about this book so far?

Monday, October 3, 2016

First Part/Last

BELLWORK: Prepositions

Go to library and get First Part Last.

HOMEWORK: Read the book for Tuesday's class 10/11.

Work on animated poems.

All late work (study guides and stories) need to be turned in for credit.

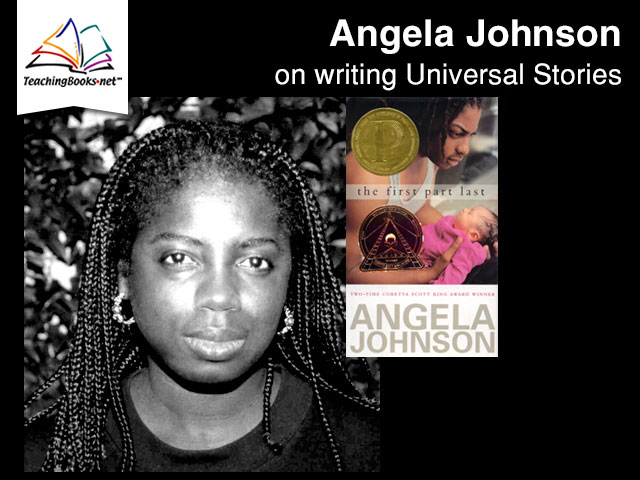

Check out the link to Angela Johnson's website.

Angela Johnson Links

![[angela_johnson.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi-WgdizGD1mnxLz-IvmzWz_0QPpe7pJcV4HqXcTHqCAK9l8uLV7wcvEeywDNq-w8w5f4l_LYOss3VtXgx6xNC5dtk2dN9yd2Vatynml_ghJj3zZWnVoJYVR51va5y36-2rXqwJjOa-wzyd/s1600/angela_johnson.jpg)

Link to Angela Johnson:

http://authors.simonandschuster.com/Angela-Johnson/1263944

http://www.ohiochannel.org/MediaLibrary/Media.aspx?fileId=126267

http://www.ajohnsonauthor.com/

http://www.teachingbooks.net/slideshows/johnson/Reads_FirstPartLast.html

http://thebrownbookshelf.com/2009/02/08/angela-johnson/

Interview w/ Angela Johnson

Angela Johnson

In-depth Written Interview

Insights Beyond the Slideshows

Angela Johnson interviewed while in Madison, Wisconsin on October 6, 2005.TEACHINGBOOKS: You've won the Coretta Scott King Author Award three times — for Toning the Sweep, Heaven and The First Part Last. Your book, Heaven was written before The First Part Last but is a sort of prequel to it. How did you come to write The First Part Last after having already written Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: The wonderful thing about The First Part Last is I didn't want to write the book at all. As far as I'm concerned, I don't do prequels; I don't do sequels.

Then, I went to New York and visited some after-school programs for a week. I was on the subway and there was this beautiful kid. He looked about 15 or 16, and he was with a baby. It was 11:00 in the morning, and I was thinking, "Why is this kid not in school? Is this his daughter; is this his sister? What's the deal?"

The train stopped, and he got ready to get off the train, I actually wanted to follow this kid down the street and question him. Something came over me. I went back to the hotel and wrote three chapters of what became The First Part Last. I felt provoked, and I didn't want it to happen. Sometimes it just comes over you and there is the story or the character. The First Part Last was the easiest book I've ever written. Bobby was just there. Everything was there.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The First Part Last, like many of your books, carries some heavy messages, though your writing never comes off as preachy.

ANGELA JOHNSON: Preaching to teens about teenage pregnancy is like preaching to a lamp. These are human beings, and they do what they want.

The First Part Last is definitely a cautionary tale, but it's not preachy. Bobby loves his baby, but what has he lost? He's lost the love of his life at 16. He's lost many of his freedoms. His friends still love him, but he's lost part of that relationship. He's lost being a child, because he is now the daddy. I always figure, show what's real — you don't have to preach. I love Bobby's responsibility. He has almost a romantic belief that, "I've lost Nia, so I'm going to raise this baby." It's noble. But then reality sets in, and some of it is not pretty.

The majority of parents have said they like The First Part Last. But, I have had parents say, "I'm not letting my kid read this book because it'll give them ideas." I said, "Ideas about going into a coma? Ideas about having this baby who's weighed you down and you've lost your childhood?" I mean, which idea? Obviously these people haven't read the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Will you write about any other characters from Heaven?

ANGELA JOHNSON: Yes. One more book — it's called Sweet. It's about Shoogy. Shoogy is still unknowable to me. I'm writing about her, and yet I still don't really know her. She is an enigma.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also write and have written many picture books. Where did your idea for A Sweet Smell of Roses emerge from?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I based the two little girls in A Sweet Smell of Roses on two real little girls who had marvelous spirit and participated in civil rights marches. In the documentary called Eyes on the Prize, two women were interviewed who were around seven and eight during the civil rights movement. They shared their experiences about how they would go off to marches without their parents. The wonderful thing is, the adults around them took care of them as if they were their own children.

Something really interesting happened in the creation of A Sweet Smell of Roses. In creating picture books, there's usually little or no collaboration between author and artist. The illustrator, Eric Velasquez, was selected by my editor; I never did share anything to him about why I wrote the book. Would you believe, Eric included artwork from the Eyes on the Prizedocumentary, and he wrote a foreword for the book about the documentary's filmmaker. It's just this bizarre kismet.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Several of your books don't have happy endings. How do you respond when people point this out?

ANGELA JOHNSON: At the end of some of my books, everything is not always happiness and light. Life is not always this big, jolly party. It is just life, and it just goes on. But I always like to leave the end as a beginning. It's not necessarily happy, and it's not necessarily sad. It is just life. I'm a happy person, but I'm a realist and I write contemporary realism.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also like to include humor in your books.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe there should be more fun books with African-American children in them. We're inundated with family stories and folk tales and the happy family. I understand that; I write those books, too. But there has to be a place for humor.

I love humor in any way, shape or form. Where Have You Gone, Vivian Dartow is going to be my funny book. Writing this book, I relived high school all over again — I thought I had it down, and in reality, I was just the biggest nerd.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you're stuck?

ANGELA JOHNSON: When I have trouble writing, I do everything but write. I like to travel when I'm blocked, and I usually come out of writing blocks after I travel.

As it turns out, my books are usually geographically motivated. I wrote A Cool Moonlightwhen I was in Aruba. I was on a beach with lots of sunlight writing a book about a child who can't go out in the daylight. I had just come back from Cape Cod when I wrote Looking for Red. The First Part Last came from New York, and Toning the Sweep came from when I was in the desert with my brother. Bird is the one book that was written when I was loving being at home.

There's always going to be something in life that will ignite you. I always believe that. It's going to be a newspaper article. It's going to be something you heard at the supermarket. It's going to be something you felt when you were going for a walk.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What other influences make their way into your writing?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have two nieces and a nephew. When they were much younger, their presence in my life had an interesting effect on my writing. I took care of them a lot, and it gave me a sense of the world of children. It was wonderful. As they get older, I see myself writing books for older children.

It has always been important in my books that the adults can be even a little emotionally neglectful or just living their lives, but in the end there is a safety net with them. In a wonderfully healthy adolescence and teen world, your parents are there — they're supportive, they're loving, they're not too obnoxious — and you go on about your life. When you're home, you're secure and they're there and they leave you alone and then you go out again. I had a huge safety net in my parents as a teenager.

Every book has pieces from my life. For instance, all my nieces and nephews are biracial. I have gay friends who have children. I had a friend whose child ran away. I take looks around me. Another example is that a female friend of mine died, and one of her children kept thinking she saw her, as a ghost out in the garden. There are so many things that I've incorporated in my books. Obviously, these are subjects that I care about and are important.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to talk with students about?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I always ask if any of them journal. I find journaling is a touchstone. When kids do that, they are secure in their writing. There are kids who, as far as they're concerned, writing stops when they leave the school. But, there are kids who are putting down any feelings they have; they're raging on paper. I say not everyone is going to be a writer, but everyone can write. No one ever has to see what they've written.

I tell them "We're not all going to be published, but your emotions — all of you have such strong emotions! Start journaling and become comfortable with what you feel. Write it down and remember. If nothing else, when you're 40 you can laugh about it like I do when I look back at mine."

TEACHINGBOOKS: What sorts of things happen when young people write-?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I'm amazed by teen poets — the poetry slams are just amazing. I am in love with the idea of teenagers getting up there and just going for it. The kids who are participating in poetry slams are the ones with something deep about them, and in recent years, now have this incredible outlet.

When I was in school, if there were some guys who were poets, I didn't know it. Now you're seeing these young men who are. I love that they're being handed the power to do something positive.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Have you ever run up against censorship of your books?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I have been asked not to come on author visits. I don't know that I have been banned.

One private religious school asked me not to come because in Toning the Sweep I talk about lynching — not graphically, of course, but I do talk about lynching. Even though I was going to speak to their elementary-aged children, who were too young to have read the book, they said, "We just need to know that you will not mention that book." I said, "No, I'm sorry, I can't do that." So they asked me not to come.

Last year in Michigan, I was speaking to a library reading club, and a couple days before I came, the aide associated with the club decided to call the parents and tell them that in The First Part Last, which was one of the books that the kids were reading, I had "language." She made calls to the library board, she called the parents, and she got nothing. Everyone felt the book was age-appropriate — what kids don't speak like this?

The reasons for banning books are just ludicrous to me. It's interesting to me that the last thing that is banned is always violence. Sexuality, language and content are banned. Violence is not. You can blow up a few buildings, and you can have people dragged down the street. People will stick guns in their children's hands and send them out in the woods to shoot animals, but they don't want to hear about sex. It's so ridiculous.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe your writing process.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I like to write longhand on legal pads. I just stick my legal pad in my backpack and go down to the park. Nowadays, everybody's in the coffeehouses on their laptops. That really freaks me out. I just started with a computer a couple years ago, but I think I'll always have the legal pads with me as well.

I lost the first half of Toning the Sweep on a word processor with no hard drive in it. It was before I understood about hard copies. I lived in a neighborhood next to an elementary school that always used to blow the electricity. At least twice a day the electricity on the whole street would go out. And there I was, page 47, I remember it vividly, had not printed anything. Everything was saved on a disk. I didn't push the little "s." The electricity went out, and it was all gone.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to write in such a wide variety of formats (picture books, poetry, novels)?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I lucked out in the beginning of my career with my editor, Richard Jackson. He never told me that I had to make choices. He never said, "You write picture books." There was never a time when he said, "You can't write poetry or short stories." I have a collection of short stories. I wrote board books. Anything I wrote, he said, "Okay."

Then, I started meeting other writers and saw that there are people who just write novels. I know I sound naïve, but I was surprised that they just write novels or they just write picture books or they just write poetry. I thought it was a given to write whatever I felt like, and I thought everyone did it. There are no parameters for me, which is wonderful. The only thing I won't touch is adult literature. But as far as kids' stuff is concerned, preschool to teen and all forms in between are great.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you believe is the importance of writing books with African-American protagonists?

ANGELA JOHNSON: I can equate it to the first time I was in school and I picked up a book by Ezra Jack Keats. I opened a book and there were children who looked like me. I cannot tell you the world that opened up. When I was a child, Ezra Jack Keats' books were the only ones with African American children in them.

What he was doing was looking out his window and these were the children he was seeing. It doesn't matter that he was white. There was a little girl in a tiny library in Ohio — me — who opened up this book and saw someone who had my skin color.

In all my books, though the stories are universal, the protagonist will likely be an African-American child, because I remember that feeling of being in a sea of books where no one looked like me. My textbooks did not have any African American children. Finally in the '70s I started to see books with African-American child protagonists, including the book Cornbread, Earl and Me.

Even though I want this to be a universal experience, I love the idea that there is an African-American child saying, "This belongs to me. Someone has recognized that kids who look like me are important and valid."

I've gone to schools that were mostly white, and I've had children ask me, "Why do you just write books with black children?" I say, "I'm African American, and I'm writing through my eyes." And then I say, "When you go into your library, how many books do you pick up that have kids who look just like you?" And they always say, "Yeah, there are a lot of them, aren't there?" Then I say, "Don't you think you need a few more like these, too?" And they say, "Yeah, okay."

TEACHINGBOOKS: Despite an emphasis on African-American characters, the themes and emotional journeys in your books strike a universal chord.

ANGELA JOHNSON: I believe we're all connected. One of the big problems in this country is people don't always feel that they are connected. We're all on this road together, bumping into each other, and we're all so connected. We have been thrown in this place. There has to come a time where we say, "It doesn't really matter if he's black or if he's Asian or if he's white. This is a universal story."

In the end what I want is for anyone to be able to pick up one of these books and it doesn't matter: the color of the children, where they live. All of these stories are everyone's story. If anyone can pick my book up and say, "Yes, this is just a wonderful story; I've felt this; I knew someone who felt this," then I've done what I was supposed to do. What else is there? It's great. It's better than ice cream.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Montana 1948 Readings/Natalie Goldberg Test 1 "I remember"

Montana 1948 Readings/Natalie Goldberg Test 1 "I remember" Marcy Gamzon • Sep 21 (Edited Sep 21) 100 points Due Tomorrow AGENDA:...

-

Choose ONE of the following topics and discuss it in a well-developed essay. You may use your book to provide text-based details. Post yo...

-

Welcome Back, Creative Writing Majors! AGENDA: Welcome to SOTA's Creative Writing Lab and the Creative Writing program. Ms. Ga...

-

AGENDA: 1. Welcome and Introductions Welcome to SOTA's Creative Writing Lab and the Creative Writing program. Welcome video: htt...